Irene Dickinson: The Woman Who Shut Down the Indian Point Nukes

Bursts of sun broke the late February chill, warming the 200 anti-nuclear activists who gathered to protest the Indian Point plants in Buchanan, NY. Skull and crossbone picket signs dotted the demonstration. A congresswoman, a New York State assemblyman and a former attorney general addressed the crowd. Nuclear power is a threat to the environment and the community, they said, and demanded major federal investment in alternative energy. Crowd chants of “shut it down” punctuated the afternoon.

This was not 2018. It was February 29, 1976.

On the other side of a police line, a counter-demonstration of 600 electric utility workers and local residents shouted down the protesters with yelling and vulgarities. Thanks to James Joy, business manager for the utility workers union, they were well-supplied with American flags and placards. Most read “Utility Workers Local 1-2 supports jobs.” A four-foot wide banner appeared, “Bella close your mouth and stop polluting the air,” as Representative Bella Abzug took the podium. The porch above Johnny Rit’s Bar and Restaurant was shoulder to shoulder with pro-nuclear chanters. Things threatened to turn ugly when the utility forces began to strain against the police line.

On the other side of a police line, a counter-demonstration of 600 electric utility workers and local residents shouted down the protesters with yelling and vulgarities. Thanks to James Joy, business manager for the utility workers union, they were well-supplied with American flags and placards. Most read “Utility Workers Local 1-2 supports jobs.” A four-foot wide banner appeared, “Bella close your mouth and stop polluting the air,” as Representative Bella Abzug took the podium. The porch above Johnny Rit’s Bar and Restaurant was shoulder to shoulder with pro-nuclear chanters. Things threatened to turn ugly when the utility forces began to strain against the police line.

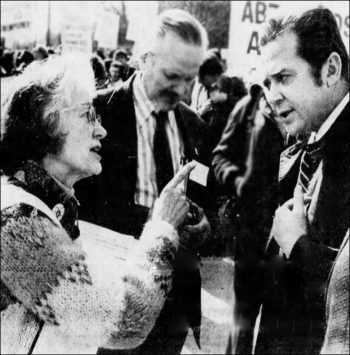

Irene Dickinson, coordinator of the anti-nuke demonstration, did not take the speakers’ microphone that day. She instead positioned herself at the center of the pro-nuke fray in order to confront Joy. A photographer captured the moment – a fearless Irene, 60, with index finger pointed at the union leader, castigating him for enlisting workers to support what she believed was the single greatest threat to the planet. She clearly had the upper hand; Joy was pointing his index finger back at himself.

“Speak truth to power” is a much abused phrase these days, applied equally to Black Lives Matter activists (who earned it), and millionaire cable talk show hosts (who haven’t). Irene believed an advocate belongs face-to-face with her adversary, no matter the odds. Her anti-nuclear force was outnumbered by an epithet-spewing 3 to 1, and she was surrounded by an angry union maelstrom, but for her the confrontation was necessary, and a solid victory. They had put on notice the owners of Indian Point 2 and 3 – Consolidated Edison and the Power Authority of the State of New York — and she had delivered a person-to-person message to the union rank and file. The following September, Family Weekly, a national Sunday news supplement, reported on the demonstration in scores of papers across the nation, from Panama City, Florida to Rapid City, South Dakota.

The backbone of the anti-nuclear movement was predominantly women. ~ Attorney Anthony Roisman

Given the dramatic sway in opinion since, it must be difficult for many to fathom how lonely was the anti-Indian Point campaign that Irene began in the late 1960s. Support for nuclear power was virtually unanimous amongst federal agencies, the governor, state agencies, county executives, local towns and villages, unions, and the general public. Undeterred, she traveled the lower Hudson River Valley, meeting with dozens of groups and gatherings, no matter how small, in churches, libraries, schools and meeting halls. Sometimes, she brought along a nuclear expert or a film, as she did on November 8, 1970 at the Rockland Ecological Coalition where she was three items down the agenda behind a recycling crisis and newspaper clean-up days. On July 20, 1974 she travelled solo to a meeting of the Lakeside Nature Center in Spring Valley where only twenty people showed up. To Irene, any meeting where anyone sat still was worthwhile.

Renowned activist Connie Hogarth, then executive director of the Westchester People’s Action Coalition, which helped organize the 1976 demonstration with Irene’s Citizen’s Committee to Protect the Environment, calls her “the mother of the anti-nuclear movement.” Attorney Anthony Roisman represented National Intervenors, an organization of sixty local and national anti-nuclear and environmental groups Irene helped organize. He told EarthDesk:

The backbone of the anti-nuclear movement was predominantly women. I always felt it was not coincidental. Themes like jobs resonated with men. What resonated with women was these plants are dangerous and unsafe. Irene was a natural leader. She was smart and savvy. She worked tirelessly day and night. If you were crosswise, she was quick to the point. But she didn’t do it in a graceless way. Once, when Indian Point hearings were held at a retirement home near the plant, she brought sandwiches for all of us, including Con Ed.

The impact of Irene’s pioneering work extended beyond Indian Point and Buchanan, NY. Governor Nelson Rockefeller’s administration, which gave us the now defunct Atomic and Space Development Agency, launched plans to transform the Hudson River Valley into nuclear power alley, including four additional plants at Lloyd in Ulster County, two at Red Hook in Dutchess County, and one at Cementon in Greene County. As anti-nuclear fervor emanated out from Buchanan, NY, other activists were inspired to take on the pro-nuclear state agencies and private industries. Not one more nuke broke ground.

Many took a bow when New York Governor Andrew Cuomo pledged to shut down the Indian Point plants. I don’t recall anyone mentioning Irene Dickinson. She was a mentor during my early years of environmental activism. I attended meetings at her home where she served comfrey lemonade and egg salad sandwiches, and I attended the February 29, 1976 demonstration she organized. If Irene were alive today, she would not have been among those taking credit. She always placed the issue ahead of herself. Still, the day Indian Point closes, a statue of Irene should be erected at the front gate — not as a memorial, but to stand guard. She would hate the idea — but far less so than the adversaries her legacy outlived.

At a time when our government is methodically working to undo every inch of environmental protection we have achieved over the last forty years, this is a timely call to action!