“HOW DOES A CITY OF THIS MAGNITUDE bring young students to the water, and have them feel a sense of ownership and community?” asks Professor Lauren Birney from her lower Manhattan office at the Pace School of Education.

“Oysters.”

A century ago, the oyster was New York’s pearl. Oystering was as integral to New York Harbor’s identity as the Statue of Liberty. The waters of the city and New Jersey boasted more than 260,000 acres of oyster beds spread throughout the harbor, its bays and estuaries, the lower Hudson and East rivers. New Yorkers ate more oyster meat than beef. The original New York “foot-longs” were Gowanus oysters, gathered from Gowanus Bay and Creek in Brooklyn and exported to Europe as a delicacy.

In present day New York, oysters are better associated with the Oyster Bar in the cellar of New York’s Grand Central Terminal, where oysters from Apalachicola Bay in Florida and Chincoteague Bay in Maryland are now the delicacy. Generations of pollution drove out New York oystering, and today the name “Gowanus” is identified less with the bay and more with the canal, a toxic, Federal Superfund site (hopefully on its way to a major cleanup).

But the Billion Oyster Project, the brainchild of the New York Harbor School, aims to change all that by enlisting hundreds of thousands of city school children to restore a billion oysters to city waters. “In short, students are driving the restoration of New York Harbor,” said Birney.

With a $5M grant from the National Science Foundation Birney is co-leading a powerhouse group of collaborators to build upon the Harbor School’s project and target “middle-school students in low-income neighborhoods with high populations of English language learners and students from groups underrepresented in STEM fields [Science, Technology, Engineering and Math] and education pathways.”

Murray Fisher, founder of the Harbor School and now president of the New York Harbor Foundation, which helps fund and manage the school’s programs, told Grist :

There are 1.1 million kids in the New York City public school system and the New York Harbor is still one of the richest water habitats in the world. But it’s become very degraded and disconnected from those 1.1 million kids.

Students from the Billion Oyster Project, Lola Boone and Ashia Salgado, with 100,000 oysters that spent two years in the nursery in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and were destined for a restoration site at the mouth of the Bronx River.

The collaborating organizations are as blue-ribbon a list of partners as one can dream up. Along with Pace University School of Education and the New York Harbor Foundation: New York City Department of Education, Columbia’s Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory, New York Academy of Sciences, Good Shepherd Services, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science,Wildlife Conservation Society’s New York Aquarium, and The River Project

Lauren and I talked about the Billion Oyster Project and the exciting challenge ahead.

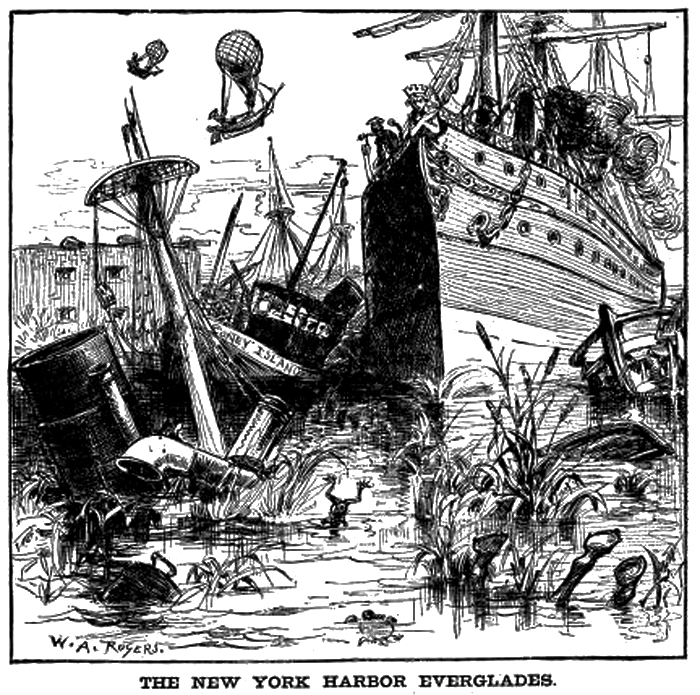

John Cronin: By the late 1800s, New York Harbor was already being lamented. Harper’s Weekly was fond of running cartoons about how fouled it was and a federal law, the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899, was enacted to control the abuse. But here we are, still talking about the harbor’s poor condition. Pairing a middle school education with its restoration is ambitious by any measure. How do the two fit together in the Billion Oyster Project?

Lauren Birney: City students benefit enormously from an increased awareness about their ecological place. Water defines New York City; it’s surrounded by it. Our young students will lead the community in the Billion Oyster Project, and get to understand first-hand what it means to make a real difference. They will earn a unique sense of ownership in their local and water community because they are the ones who are driving the restoration.

Cartoon accompanying Harper’s Weekly article, “The Garbage Blockade,” June 30, 1883.

JC: In addition to the students’ work constructing reefs, growing and planting oysters, and operating monitoring equipment, the $5 million National Science Foundation grant is designed to translate that hands-on experience into a curriculum for the city school system. How?

LB: The harbor is like a living laboratory for education in STEM. We want to give students the opportunity to learn outside the school building. Our consortium of partners is creating opportunities for citizen science, real-time data collection, operation of monitoring technologies, and more. After-school mentoring provides extra enrichment for those students especially interested in STEM. Maybe a student gets excited about oysters or the condition of the harbor and decides to be a biologist, or pursue an interest in maritime law. An interest in our monitoring technologies could open a door to the study of engineering. These experiences are such a rarity for our students they may otherwise not have the opportunity to discover their passion.

JC: I know from experience it is not always easy to integrate such innovative education into the standard public school curriculum. Is that a challenge?

LB: Yes. But we have a great partner in the New York City school system, and a strong emphasis on teacher training. Over the next 18 months we expect to work directly with 40 teachers; each has 30 – 35 students. And those teachers are sharing with other teachers, such as English teachers. This is such a rich area of pedagogy it can infiltrate through all subject areas.

JC: Will it work?

LB: There are always a million reasons why something this ambitious won’t work. But you only need one reason why it will. Our incredibly talented partnership is entirely focused on it working — and it already is.

There is yet another reward to the Billion Oyster Project. Fisher’s vision did not end at tying education to oyster restoration. Just as pollution was the enemy of the New York Harbor oyster, the oyster can be the enemy of New York Harbor pollution. One oyster can filter one gallon of water each day, as he explained to The Wall Street Journal this summer:

Theoretically, if we have a standing population of one billion oysters, the harbor would be completely filtered every three days.

The Billion Oyster Project not only empowers students to build a new future for their community, it enables them to connect their present to their past, while reflecting upon, and redeeming, the unwitting misdeeds of prior generations.

As I discussed this with my Pace colleague Lauren Birney, I was reminded of the teachings of Ernest L. Boyer, the great American educator and adviser to three presidents. He wrote in Hope for Today’s Universities:

While we are all nonuniform and while we differ dramatically from each other, the simple truth is that all the people on the planet have the marvelous capacity to place themselves in time and space. We can recall the past and anticipate the future. And yet, how often we squander this truly awesome capacity to look in both directions, even neglecting our own roots.

A paragraph later comes his most enduring quote — his simple solution to that intergenerational dilemma, a central tenet of his theory of education taught him by his grandfather who devoted his life to underserved communities:

To be truly human, one must serve.

Ultimately, the Billion Oyster Project is about service: to the environment, to school children, to a city that lost its environmental way, to those of a long-gone generation who knew not what they were losing, even as it slipped through their fingers.

If you would like to be part of this brilliant, groundbreaking effort, join Professor Birney and John Forest Dohlin, director of the New York Aquarium, on October 27: