Legislator Patrick B. Burke: “I knew I had to do something.”

Polyethylene may be the most common plastic on the planet but Erie County, NY says cosmetic companies have gone a step too far marketing personal care products containing the millions of plastic particles that end up in Lake Erie fish.

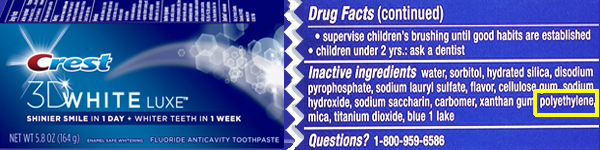

MICROBEADS are spherical particles of polyethylene present in thousands of personal care products — toothpastes, shampoos, lotions, exfoliating skin scrubs and more. Some products proudly display the words “with microbeads” on their labels, promising whiter teeth, brighter skin or glowing hair. All must indicate the presence of “polyethylene” in the ingredients list.

The packaging for Crest 3D Whiteluxe (above) even appears to depict pieces of the glittering plastic with which you are about to brush your teeth. The Buffalo News reports the experience of one dental hygienist:

Sarah Lewis can always tell when one of her patients uses Crest 3D White toothpaste – she finds the toothpaste’s tell-tale tiny, blue microbeads trapped between their teeth and gums.

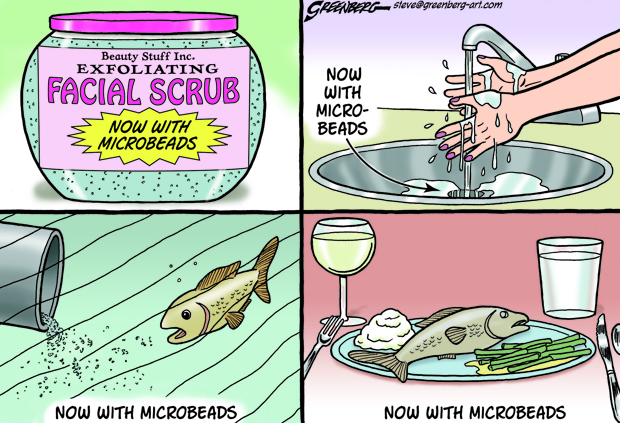

Microbeads are also present throughout New York State waters, by the millions of tons, according to a report by New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman. They can be found in fish organs, tissue and bloodstream. Other toxins, such as PCBs, cling to them, further contaminating fish and endangering public health.

After you finish washing, scrubbing or exfoliating, the almost microscopic plastic bits wash down the home drain and out to the local sewage treatment plant. But of New York’s 610 wastewater plants 403 have no capacity to remove microbeads, and the other 207 are questionable. The Schneiderman report singled out Erie County as an example:

In Erie County, population 919,000, residents unknowingly discharge almost one ton of microbeads into the wastewater stream each year. Most Erie County residents’ wastewater travels to a local plant for treatment. The largest wastewater treatment plant in the county has the capacity to service 600,000 residents in and around Buffalo. It also does not employ advanced screening or filtration, and its effluent discharges into the Niagara River.

Microbeads by Steve Greenberg. Cagle Cartoons. Used with permission.

Schneiderman proposed a Microbead-Free Waters Act that eventually passed the New York State Assembly but became trapped in the Senate amidst a legislative session torn by ethics scandals. Erie County Legislator Patrick B. Burke decided to act locally. He told EarthDesk:

I’ve been an environmental advocate since entering office. I read the Attorney General’s report on microbeads and I found it shocking. When the common sense legislation stalled out in the State Senate, I knew I had to do something.

He introduced the Local Microbead Prohibition Law, which passed the county legislature unanimously on July 30. It was signed into law on Wednesday by Erie County Executive Mark C. Poloncarz.

According to The Buffalo News:

The county’s ban on microbead plastics – believed to be the most comprehensive in the country – would result in the removal of more than 100 consumer products from retail stores.

[…]

Erie County residents swearing by their Crest 3D White or their favorite facial scrub or moisturizer may have only a little more than six months to either stock up on those products, buy them online or find a different cleanser or toothpaste.

After years of fighting back, the cosmetics and personal care product industry is being worn down by the international anti-microbead campaign. Increasingly, mainstream consumers are pressing companies for an answer to why they should scrub their skin with pieces of plastic that then contaminate local waters.

We asked Legislator Burke if the industry mounted a campaign against the Erie County initiative.

We didn’t find overwhelming opposition from the cosmetics industry. The little we did wasn’t compelling when compared to the potential harm to our ecosystem.

21 companies worldwide have pledged to phase out microbeads voluntarily, or find a substitute. But public officials like Burke and Schneiderman believe only legislation will reliably stem the flow of the tons of plastic that wash down home drains. In recommending a state statute, the Schneiderman report concluded:

[W]ith many current industry commitments lacking a phase-out deadline and with many more companies still unresponsive, additional effort is needed to hold the industry to a consistent, protective standard.

For now, however, protection of state waters from continued microbead contamination looks to be in the hands of conscientious local legislators like Patrick Burke.