Editor’s Note: Climate Central is an independent organization of leading scientists and journalists researching and reporting the facts about our changing climate and its impact on the American public. Its scientists publish and journalists report on climate science, energy, sea level rise, wildfires, drought, and related topics. This post appeared on Climate Central, March 23, 2015. More on John Upton at the conclusion.

A sweeping ocean conveyor system that ushers warm tropical waters into the North Atlantic appears to have partly recovered from a near-collapse around the time that the Beatles were breaking up, but the system remains weaker than it had been since before humans figured out how to write modern music on a page.

Powerful Atlantic Ocean currents fuel Gulf streams, affect sea levels, warm cities in continental Europe and North America, and bring nutrients up from ocean depths that help sustain marine ecosystems and fisheries.

But an avalanche of cold water from the melting Greenland ice sheet appears to be slowing the ocean circulation to levels not experienced in more than 1,000 years.

The NY/Tri-state area is defined by the ocean’s influence. From the top of the image, the tidal Hudson, which drains from the north on its way to the Atlantic, borders western Westchester County, NY and New York City, and eastern Rockland County, NY and New Jersey. The tip of Sandy Hook, NJ juts from the lower left corner. Long Island Sound, mid-right, borders eastern Westchester and New York City, southern Connecticut and the north shore of Long Island. View from Space Shuttle Columbia, mission STS-58. Public domain.

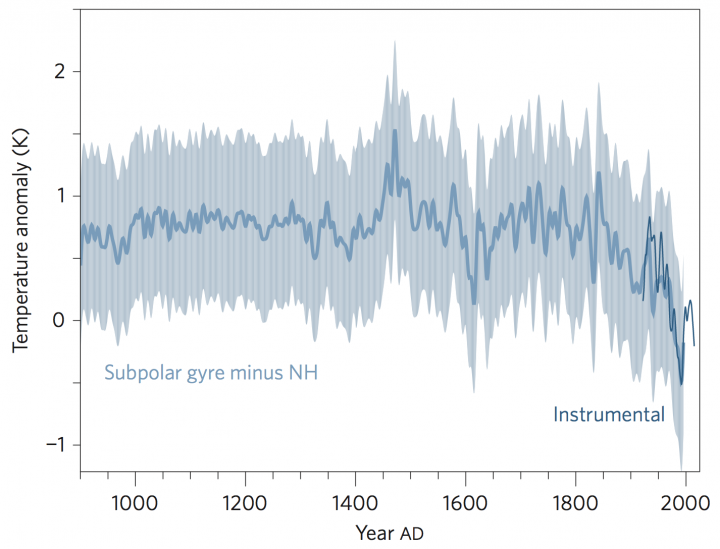

That’s the conclusion of a bold new attempt to combine temperature measurements and climate-related data scrounged from coral samples, ice cores and tree rings to track the worrying decline of the critical Atlantic Ocean phenomenon. The new research, published Monday in Nature Climate Change, used observations and studies of sea-surface temperatures to produce a new index — one that charts the waning force of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC), one of the planet’s most important circulation systems.

The index reveals a modern powering down of the AMOC, including a sharp slowdown between 1970 and 1990, which had already been widely detected, followed by a partial recovery that nonetheless failed to boost the system back to its vigorous pre-Industrial Revolution state.

The new index shows the weakening of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation.

Credit: Nature Climate Change

If the climate relationships identified by the researchers, led by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany, hold true, growing melt rates in Greenland “might lead to further weakening of the AMOC within a decade or two, and possibly even more permanent shutdown” of key components of it, the scientists warn in their paper.

The findings of the research were “dramatic,” but consistent with projections from computer climate models, Stephen Griffies, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration climate and ocean modeler, said. Griffies wasn’t involved with the study. He contributed to recent research linking abrupt AMOC changes with a historically unprecedented five-inch spike in sea levels along Northeast U.S. coastlines in 2009 and 2010. Other researchers havelinked that same AMOC slowdown of five years ago with harsh winters in Europe and with a spike in hurricane activity.

“It’s inevitable, from my perspective, that we will start to see more and more evidence for the slowdown of the circulation,” Griffies said. “If the overturning circulation slows down further, these extreme sea-level events on the East Coast will become more frequent.”

Michael Mann, a Penn State professor who directs the school’s Earth System Science Center, and one of the authors of the new study, said Greenland’s ice is melting faster than anticipated, which could explain why the AMOC appears to be slowing “decades ahead of schedule.” He said the abrupt slowdown in the AMOC around 1970 “looked like an aborted collapse” — and that a “full-on collapse” could be possible in the decades ahead.

The precise consequences of an ongoing AMOC slowdown are hard to predict, according to Mann, but he warned that it could reduce global food security by withholding deepsea nutrients from fisheries and food chains that flourish in shallower Atlantic Ocean depths.

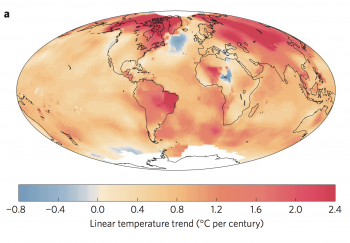

The cooling patch of ocean south of Greenland is linked to the AMOC changes underway. Credit: Nature Climate Change

“The most productive region, in terms of availability of nutrients, is the high latitudes of the North Atlantic,” Mann said. “If we lose that, that’s a fundamental threat to our ability to continue to fish.”

Without the AMOC to carry heat away from the tropics and redistribute it, Mann said parts of the Northern Hemisphere could become cooler. But he also said hurricanes, Nor’easters and other storms could become more common, providing the heat with an alternative pathway along which it can travel.

“If you shut down this mode of ocean circulation, you’re denying the climate system one of its modes of heat transport,” Mann said. “if you deny it one mode of transport, it’s often the case that you will see other modes of transport increase.”

The new AMOC index “will certainly attract a lot of attention,” said Stephen Yeager, a researcher in the National Center for Atmospheric Research’s oceanography division. He said he remained skeptical about the reliability of some of the temperature data used, and that other research suggests rising temperatures are playing more of a role in the circulation slowdown than the wash of fresh meltwater from Greenland.

“The paper presents an exciting new perspective,” Yeager said. “Many of the ideas put forth in this paper will require substantial further scrutiny and testing.”

«« »»

John Upton is a Senior Science Writer at Climate Central. He studied science and business in Australia, worked as a journalist in California, enjoyed an 18-month environmental reporting odyssey in India, then joined Climate Central’s editorial team in New York. Upton has written for the New York Times, Slate, Nautilus, VICE, Grist, Pacific Standard, Modern Farmer, 7×7 San Francisco and Audubon magazine. For more on John Upton, follow this link.

John Upton is a Senior Science Writer at Climate Central. He studied science and business in Australia, worked as a journalist in California, enjoyed an 18-month environmental reporting odyssey in India, then joined Climate Central’s editorial team in New York. Upton has written for the New York Times, Slate, Nautilus, VICE, Grist, Pacific Standard, Modern Farmer, 7×7 San Francisco and Audubon magazine. For more on John Upton, follow this link.