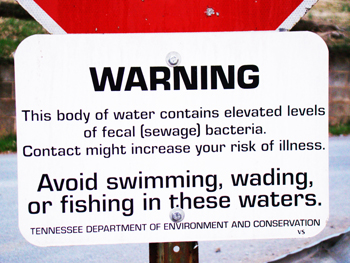

A beach on the Licking River banned for swimming by the State of Kentucky. It is one of the nation’s many inland beaches not included in the EPA Beach Advisory and Closing On-Line Notification (BEACON) system.

A continuing investigation by EarthDesk has revealed critical inadequacies in the well-known and often referenced Environmental Protection Agency Beach Advisory and Closing On-line Notification System (BEACON). The BEACON system was created in accordance with the Beaches Environmental Assessment and Coastal Health Act of 2000 (BEACH Act). The law limits reporting on swimming closures to “coastal recreation waters,” thereby excluding from the warning system thousands of acres of inland lakes and thousands of miles of inland rivers that contain public beaches.

For a series of posts on EarthDesk, we researched a sampling of the excluded public beaches. Our findings were startling. Hundreds if not thousands of lost beach-days due to closures on inland waters go unreported by EPA. In some cases, outright violations of the Federal Clean Water Act caused the closures. For example, the State of Kentucky explains that its years-old closures on the Kentucky River, Upper Cumberland River and Licking River are in part due to chronic contamination caused by:

[I]llegal straight pipe discharges, failing septic systems and bypasses from sewage collection systems.

In another example, Tennessee declared unsafe 176 miles of river, including an area of Beaver Creek, one of the state’s most popular paddling and swimming destinations. According to Tricities.com:

In another example, Tennessee declared unsafe 176 miles of river, including an area of Beaver Creek, one of the state’s most popular paddling and swimming destinations. According to Tricities.com:

Eighteen people in Northeast Tennessee and Southwest Virginia were diagnosed with E. coli infections between May 8 and June 11, [1983] including Gabby Blair, a 2-year-old girl from Dryden, Va., who died June 5 after she was rushed to Johnson City Medical Center’s Pediatric Intensive Care Unit with HUS [hemolytic uremic syndrome].

EPA, environmental groups and others typically use the BEACON system to calculate the total annual number of closed beach days nationally, to assess the overall quality of the nation’s swimming beaches, and to evaluate the success of the EPA and Clean Water Act in achieving the national goal of waters safe for recreation.

But all such conclusions drawn from the database are inaccurate, due to the limited number of beaches, and states, that are included in the system. And the continued use of BEACON by EPA and others as if it were statistically definitive, misleads the public, nationally and locally.

The links below are a compilation of articles we posted last summer that document case examples of inland waters that did not qualify for the BEACON database and were declared a hazard to human health. First, we begin with an analysis of the Clean Water Act’s failure to achieve the dual goals of eliminating pollution and guaranteeing water quality that provides for safe recreation:

– The 31st Anniversary of the Clean Water Act’s Failure to Achieve Its First Policy Goal

– Local TV Warns of Years-Old Kentucky Swimming Advisories; EPA Does Not

– 23% of Ohio River Samples Unsafe for Swimming but Absent from EPA Database

– Illness, Death and Swimming in Tennessee: E. coli Takes Its Toll; No Advisory from EPA

– 12% of Iowa Swimming Beaches Unfit, but not Included in EPA Database

– Abison Numangu by the Guam Environmental Protection Agency