We Are Not All Environmentalists, Nor Must We Be. A Post-Election Reflection

In the difficult years ahead, environmental organizations should address the social inequities challenging millions of Americans — a founding principle of American environmentalism.

In the shadow of the celebrations and recriminations that followed the 2016 presidential election, an important discussion is taking place about a neglected piece of America and how it voted. The environmental movement should take heed.

A fractured nation emerged more divided after Donald Trump’s decisive victory in the Electoral College.[1] Overnight, demonstrations broke out in major cities.[2] Hate crimes were on the rise.[3] Accusations of racism and misogyny, elitism and fraud were fired like so much birdshot into the virtual public square. Bigotry populated Twitter,[4] and on Facebook accusatory posts and broken ties with family and friends were commonplace. Environment has been a frequent topic — of concern and division, mostly the latter.

Candidate Trump was clear about his intentions. He called climate change a hoax perpetrated by China,[5] and pledged to radically retool the Environmental Protection Agency.[6] President-elect Trump then appointed climate change antagonist Myron Ebell of the Competitive Enterprise Institute to oversee the transition of the EPA.[7] If the new administration so chooses, it can set back American environmental policy two generations by use of executive authority alone.

Many have demeaned the voters who delivered the Electoral College to Mr. Trump as hate mongers and uneducated, but the stereotypes are crumbling. It was the Rust Belt, the South and rural America that brought the win, and Secretary Clinton is enduring intense criticism for having focused her attention elsewhere, on a narrow demographic she believed would eke out her victory.[8] In so doing, she sealed her political fate.[9] With some self-reflection, environmentalists can learn from her missteps.

There are people in America whose personal circumstances leave them little room to identify as environmentalists.

A recent story on the Smithsonian Magazine site is illustrative. In its “The Age of Humans” section, the magazine devoted an eye-grabbing headline and photo to a Generation Anthropocene podcast with writer Kim Stanley Robinson.[10] The thirty-six minute audio file was posted as well. Here is an excerpt at the 8:00 mark:

Host: Would you call yourself an environmentalist?

Robinson: Oh yes. Sure.

Host: Without hesitation?

Robinson: No, of course not. No hesitation at all. To me, either you’re an environmentalist or you’re not paying attention, or you’re in denial somehow.[11]

Smithsonian broke out that last sentence in large boldface as a sub-headline. Reposts of the quote then appeared on 150 or more online forums. Robinson’s careless language – if you are not an environmentalist you are clueless or uncaring – combined with Smithsonian’s tacit endorsement, is indicative, no matter how unintended, of the elitism and arrogance for which contemporary environmentalism is often criticized. The fact is, we cannot all be environmentalists, nor must we be. Some people are necessarily “paying attention” to other priorities.

Approximately 43.1 million people in the U.S. live in poverty — that is, if you agree with the U.S. Census Bureau’s modest poverty threshold, which ranges from $11,367 annually for a person over 65 to $49,177 for a family of nine or more; a family of four living on $24,300 does not even qualify as poor.[12] 42.2 million people live in food insecure households.[13] 7.8 million people are officially unemployed,[14] with the real number reaching 9 million, according to some experts.[15] On any given night more than 500,000 people may be homeless,[16] and advocates say greater than 3 million people experience homelessness at some time during the year; more than half of those are children.

It is reasonable to conclude there are people in America whose personal circumstances leave them little room to identify as environmentalists. But even if you give the best benefit of the doubt to Smithsonian, Generation Anthropocene, and Robinson – that they were not addressing themselves to the millions of needy Americans who may have other priorities — it begs the question: To what audience are they speaking? It is a question as well for the entire movement.

On November 13, CBS Sunday Morning aired “The View of Voters in West Virginia Coal Country.” Senior correspondent Ted Koppell travelled to McDowell County where the clash between climate policy and the coal industry is cast in high relief. There the economy is in collapse: population has plummeted from 100,000 to 19,000, most local stores are shuttered, unemployment is twice the national average and poverty is at 35%.[17] “We’re on the bottom and we’re being totally neglected,” Sheriff Martin West told Koppell.[18]

Most heart-rending was the tearful testimony of Kristen Mitchem, an unemployed single mother of three. She sat for an interview with other community members in a local diner. Ms. Mitchem had not voted in the election. Koppell asked her, “Why the hell not?”

Mitchem: I felt that this was the most ridiculous election I’ve ever witnessed in my life. I know I’m young, but they went about it the most childish way I think someone ever could. Through the whole election I never heard either party talk about the lower class. I’m lower class. They’re worried about middle class and higher class.

Koppell: You were born here?”

Mitchem: I was born and raised here.

Koppell: So you know a lot of people your own age?

Mitchem: I do, I do.

Koppell: Is there a lot of desperation?

Mitchem: There truly is. I would never have imagined in my life that I would be in this kind of position. I don’t wanna leave my home. But I feel as if I’m being forced out of my home because there’s nothing here anymore.

Sitting next to Ms. Mitchem at the diner table, Delores Johnson, an African American and President of the McDowell County Chamber of Commerce, added, “I agree with what she’s saying. It’s sad.”[19] As happened in rural America at-large, Mr. Trump’s populist, working-class appeal handily carried McDowell County and West Virginia, once a Democratic stronghold. Ms. Mitchen was among the 43% of eligible voters nationwide who chose not to vote.

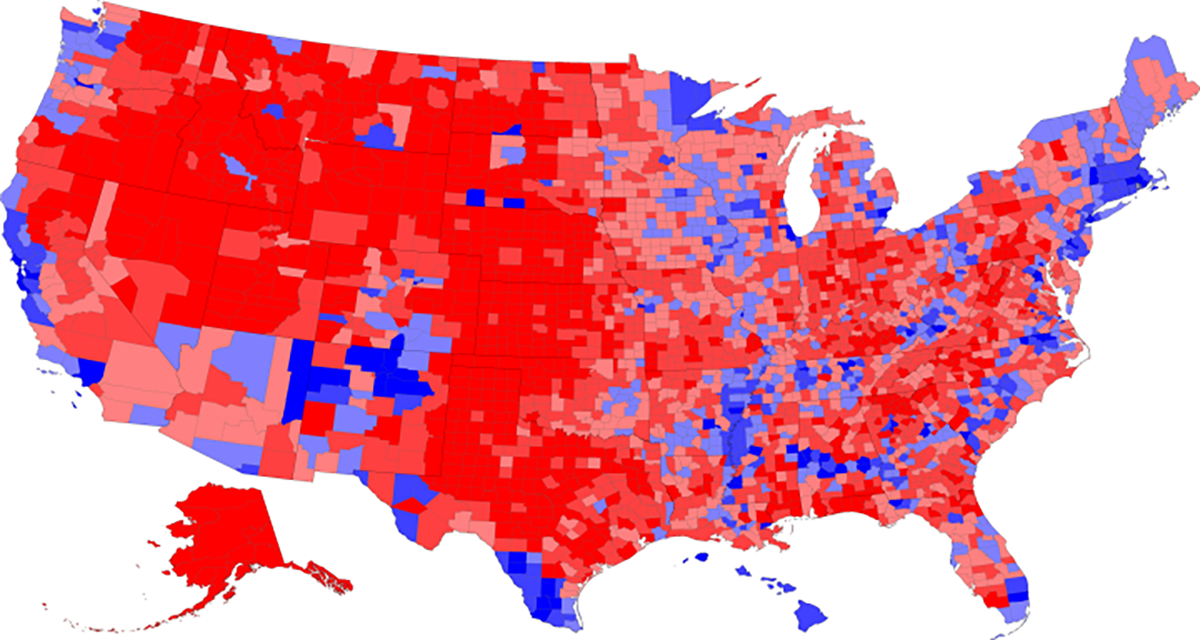

Like many, including the media, environmentalists were confident Secretary Clinton would win. The Washington Post reported that “environmental groups had been planning to immediately press a President-elect Hillary Clinton to stick to a tough set of energy and environmental policies.”[20] Although, at this writing, Secretary Clinton leads the popular vote by 900,000 and climbing, that will not affect the outcome in the Electoral College. A post-election map of the nation shows why — a sea of red dotted with islands of blue, a stunning demographic Democratic failure. With Secretary Clinton’s certain victory upended, will President-elect Trump’s surprise upset prompt soul-searching within the environmental movement?

It already has at The New York Times, where Public Editor Liz Spayd was unsparing in a column titled “Want to Know What America’s Thinking? Try Asking.” She wrote, “As The Times begins a period of self-reflection, I hope its editors will think hard about the half of America the paper too seldom covers.”[21] Margaret Sullivan, media critic for The Washington Post, wrote, “Although we touched down in the big red states for a few days, or interviewed some coal miners or unemployed autoworkers in the Rust Belt, we didn’t take them seriously. Or not seriously enough.”[22]

It is a favorite axiom that environmentalism is ultimately about “the children.” But it must be asked: Is American environmentalism about Ms. Mitchem’s three children? Is it about the 15 million American children living in poverty, 88% of whom are from minority populations? Is it about cratering local economies that drive families from their homes in places like McDowell County? Is it about the other “half of America?”

The Clinton campaign was based on the data-based design of a modern presidential race. The demographically precise pursuit of 270 Electoral College votes precluded a fifty-state national campaign in favor of a ten-state strategy. In that technical chase for victory, a large piece of America was neglected, to use Sheriff West’s word. But the environmental movement is burdened by no such strictures. It does not have to cherry pick certain constituencies over others, nor should it.

In the years ahead, American environmental organizations will campaign vigorously to hold the line on climate, water, air, public lands and more. It will be a difficult fight. As vigorously, they should launch a fifty-state campaign that reaches out to all Americans, environmentalists or not, to the Kristen Mitchem’s and the Delores Johnson’s, to all economic classes, all ethnicities, and all the disempowered who believe that casting a vote will make no difference in their own lives. Environmental organizations can begin with an educational and political agenda aimed equally at the social inequities that challenge tens of millions of fellow Americans — and a $1 full membership to any person willing to support it.

This is not a cynical ploy to win over supporters, nor is it a pitch for a new brand of environmentalism. Rather, it is a revival of the inclusive principle upon which contemporary American environmentalism was founded almost five decades ago — as has been said many times before on these pages. And so, once again, these words of Earth Day founder U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson from a speech he delivered in Denver, Colorado, on the inaugural Earth Day, April 22, 1970:

Earth Day can — and it must — lend a new urgency and a new support to solving the problems that still threaten to tear the fabric of this society . . . the problems of race, of war, of poverty, of modern day institutions.

[. . .] Our goal is not just an environment of clean air and water and scenic beauty. The objective is an environment of decency, quality and mutual respect for all other human beings and all other living creatures.[23]

Endnotes: Follow this link

«« »»

John Cronin is Senior Fellow for Environmental Affairs at the Dyson College Institute for Sustainability and the Environment at Pace University, and editor of EarthDesk.

DCISE News

Pace Students: Hands On & All In

To embody environmental values and environmental ethics is a moral imperative otherwise one would be living a contradiction where environmentalism is just as acceptable as anti environmentalism.In the same sense that one cannot and should not be a democracy advocate and yet does not have a problem with dictatorship or tyranny an environmentalist’s goal has to be a society composed of individuals driven and guided by respect for nature and environmental ethos. Real environmentalism is the only goal worthwhile shooting for, it just might be the end of history. How can it be otherwise?

“Perhaps the time has come to cease calling it the ‘environmentalist’ view, as though it were a lobbying effort outside the mainstream of human activity, and to start calling it the real-world view.” E O Wilson.