Will the U.S. acknowledge that Americans number among the world’s hungry, impoverished and health challenged?

![Sailors assigned to guided missile destroyer USS Mahan (DDG 72) serve lunch to homeless veterans at the New England Shelter for Homeless Veterans. By U.S. Navy photo by Chief Mass Communication Specialist Dave Kaylor [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://earthdesk.blogs.pace.edu/files/2015/11/mew-england-homeless-veterans1-700x414.jpg)

Sailors assigned to guided missile destroyer USS Mahan (DDG 72) serve lunch to homeless veterans at the New England Shelter for Homeless Veterans. By U.S. Navy photo by Chief Mass Communication Specialist Dave Kaylor [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Food security– access by all people at all times to enough food for an active, healthy life — is one of several conditions necessary for a population to be healthy and well nourished.

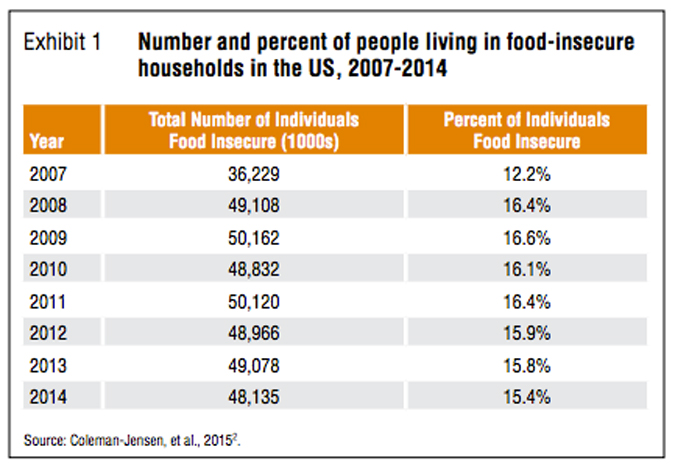

The BWI report, which includes the study Estimating the Health-Related Costs of Food Insecurity and Hunger, conducted by John Cook of Boston Medical Center and Children’s HealthWatch and Ana Paula Poblacion of Universidade Federal de São Paulo in Brazil, concludes that 48 million Americans, one in seven, lived in food insecure households in 2014. The study can be found in Appendix 2 of the report on page 183.

The chart below shows that the number of food insecure households has remained relatively unchanged since 2008. There has been a downward trend by percentage since 2012, but the fluctuations of previous years make that trend unreliable.

According to Cook and Poblacion:

[C]osts attributable to food insecurity and hunger in 2010 conservatively amounted to a total of $167.5 Billion spread over illness-related costs, education-related costs, and charity costs. The costs estimates produced for 2010 ranged from 33 percent to 38 percent higher than the 2007 estimates across these categories. As described in the remainder of this section, there is little evidence that economic conditions in 2014 were sufficiently better than those in 2010 to suggest significant reductions in the costs attributable to food security over that period

More alarming than the national statistics presented by the authors are the far higher numbers hidden in poverty hotspots. The organization North Carolina Foodbanks reports 26.1% of children below the age of 18 are food insecure in that state. In Washington DC, 30.5 percent of households with children were food insecure, according to the report Food Hardship 2008-2012: Geography and Household Composition.

Statistical anomalies are not isolated to our most impoverished regions. In San Francisco, for example, gentrification and the escalating cost of the city’s housing stock has created a subculture of food insecurity where some residents are even trading sex for food, according to a recent study from the University of California, San Francisco. Nor is geography a determinant. A study published in the journal Public Health Nutrition reported that 1 of 4 veterans are food insecure.

Each of these studies directly connects food insecurity to significant health problems, ranging from malnutrition to chronic disease; in the case of San Francisco, with the spread of HIV/AIDS.

The BWI report calls for a major policy shift where food security and health are no longer “confined to separate policy siloes.” The place to begin, it says, is the United Nations 2015 Sustainable Development Goals which link poverty, hunger, health and natural resources: “As in other countries, the United States will be developing plans to achieve the SDGs domestically.”

This may be optimistic. Despite the disturbing statistics here at home, it is debatable the U.S. will acknowledge American citizens number among the hungry and impoverished the U.N. more readily identifies with the developing world.

The report concludes:

In the 2016 Hunger Report, we call on the U.S. government to engage its domestic civil society partners who are working to address the many social determinants of hunger and health in communities across the nation. Achieving progress will depend on leaders rising to the challenge everywhere, so the federal government will need to engage state and local leaders. al leaders.

[…]

We are the generation that could see the end of hunger and poverty. The SDGs provide a bold and ambitious framework that would transform the world we live in for generations to come. It is a difficult challenge, but it is not impossible. Countries and communities around the world have made tremendous progress against poverty and other hardships. A key ingredient for success has been political leadership. As advocates, our job is to build the political will to end hunger and poverty in a way that also takes care of the natural resources we so depend on.

For more on the conclusions and recommendations of the Bread for the World 2016 Hunger Report, follow this link.