James Gustave Speth: If there is a model it is the civil rights revolution of the 1960s. It had a dream.

The dream of modern American environmentalism was founded on the dream of the American civil rights movement. You would not know it today.

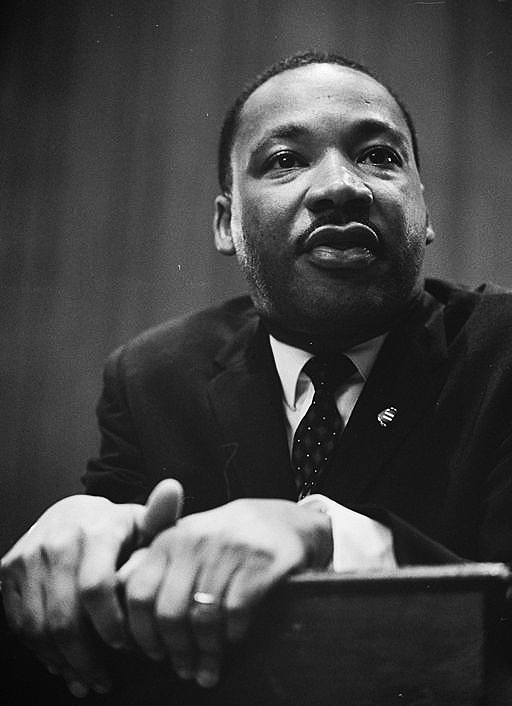

Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. Marion S. Trikosko [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.

Reverend King’s Birmingham admonition and the strains of his oratory reverberated in the environmental writings and speeches of the early 1970s, when American environmentalism was constructed around the cornerstone of justice for all.

On the first Earth Day, April 22, 1970, Earth Day founder and Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson addressed a standing room only, Denver, Colorado audience. He echoed Reverend King:

Earth Day can–and it must–lend a new urgency and a new support to solving the problems that still threaten to tear the fabric of this society… the problems of race, of war, of poverty, of modern-day institutions.

Environment is all of America and its problems. It is rats in the ghetto. It is a hungry child in a land of affluence. It is housing that is not worthy of the name; neighborhoods not fit to inhabit.

[…]

Our goal is not just an environment of clean air and water and scenic beauty. The objective is an environment of decency, quality and mutual respect for all other human beings and all other living creatures.

On that same day, in Philadelphia, Maine Senator Edmund Muskie addressed an audience of 50,000 at Fairmount Park’s Belmont Plateau. He was eloquent in his warning that social and environmental justice should not be separated:

The whole society that we seek is one in which all men live in brotherhood with each other and with their environment. It is a society where each member of it knows that he has an opportunity to fulfill his greatest potential.

[…]

We have seen the destructiveness of poverty, and declared a war on it.

We have seen the ravages of hunger, and declared a war on it.

We have seen the costs of crime, and declared a war on it.

And now we have awakened to the pollution of our environment, and we have declared another war.

We have fought too many losing battles in these wars to continue this piece-meal approach to creating a whole society.

In his masterful memoir, Angels by the River, which we will discuss further in a future post, pioneer environmentalist James Gustave “Gus” Speth writes that the civil rights movement was integral to his personal and political formation. It inspired him in 1970 to help launch a new era of environmental jurisprudence through the co-founding of the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), one of the planet’s most successful, and effective, environmental organizations.

In his masterful memoir, Angels by the River, which we will discuss further in a future post, pioneer environmentalist James Gustave “Gus” Speth writes that the civil rights movement was integral to his personal and political formation. It inspired him in 1970 to help launch a new era of environmental jurisprudence through the co-founding of the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), one of the planet’s most successful, and effective, environmental organizations.

But Speth’s reflections on the progress of American environmentalism carry a sober warning:

Our environmental organizations have continued to grow in strength and sophistication, but the environment has continued to go downhill. The prospect of a ruined planet is now very real. We have won many victories, but we are losing the planet.

[…]

In launching NRDC we set out to change the system. But we didn’t. We improved the system in places, made it safer, better. But in doing so we became part of the system. It changed us.

In addition to losing ground in the battle to save the environment, America is losing the battle against poverty, homelessness and hunger, issues in which most environmental organizations are marginally involved at best, as we have said often in these pages. Ed Muskie warned of this outcome. He called for an “environmental revolution” that “will turn the nation around,” that will also attack the scourge of poverty and the injustice of unequal opportunity.

The only strategy that makes sense is a total strategy to protect the total environment. . . If we use our awareness that the total environment determines the quality of life, we can make those decisions which can save our nation from becoming a class-ridden and strife-torn wasteland.

Speth finds the remedy to our present day dilemma in the founding vision of American environmentalism — emulation of the civil rights movement:

If there is a model within American memory for what must be done, it is the civil rights revolution of the 1960s. It had grievances, it knew what was causing them, and it also knew that the existing order had no legitimacy and that, acting together, people could redress those grievances. It was confrontational and disobedient, but it was nonviolent. It had a dream.

Here Speth also renews Senator Muskie’s call of almost 45 years ago. At the conclusion of his 1970 Earth Day speech, Muskie summarized his dream of a “whole society” by citing Reverend King directly:

Martin Luther King once said that ‘Through our scientific and technological genius we have made of this world a neighborhood. Now through our moral and spiritual genius we must make of it a brotherhood.’

For Martin Luther King, every day was an Earth Day — a day to work toward his commitment to a whole society. It is that commitment we must keep.