The National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reported on August 2 that the Arctic “continued to warm at about twice the rate compared with lower latitudes” during 2012. The news is likely causing a great sense of urgency at the White House, though not for the reasons you might expect.

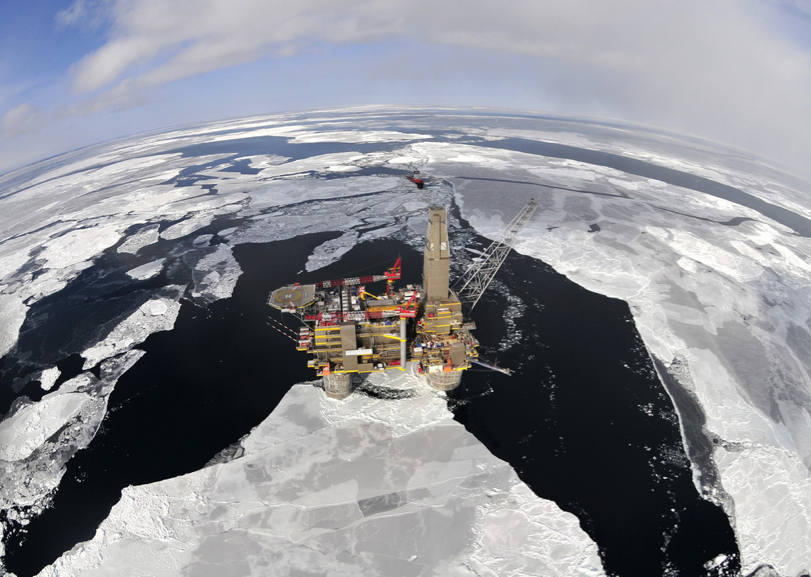

The Arctic is the biggest prize in climate adaptation exploitation. As the melting sea ice opens frozen shipping lanes, nations are gearing up for the 21st century version of the Gold Rush, and the United States is determined to stake its claim.

What others call The Big Melt (1, 2, 3), the White House sees as “emerging economic opportunities.” From its May 13, 2013 National Strategy for the Arctic Region:

The dense, multi-year ice is giving way to thin layers of seasonal ice, making more of the region navigable year-round. Scientific estimates of technically recoverable conventional oil and gas resources north of the Arctic Circle total approximately 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered gas deposits, as well as vast quantities of mineral resources, including rare earth elements, iron ore, and nickel . . . As portions of the Arctic Ocean become more navigable, there is increasing interest in the viability of the Northern Sea Route and other potential routes, including the Northwest Passage, as well as in development of Arctic resources.

There is a history of international cooperation in the Arctic, characterized by the Arctic Council (Canada, Denmark [including Greenland and the Faroe Islands], Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States), cooperative research programs, and various Arctic treaties and agreements. But that could change. From a resource exploitation perspective, the stakes have never been higher, the international competition fiercer, or the environmental liabilities greater. Sadly, in the absence of international environmental leadership, the US is not stepping into the breach.

The assertion of national defense, and air and water rights was meant to send a message that the US role as an aggressive competitor in the Arctic race would not be hindered.

With 1.1 million square miles of international waters, the Arctic Ocean is up for grabs. Though the US stands as the lone Arctic nation holdout to the Law of the Sea Treaty (more on LOST below), the White House strategy puts a calm face on the state of Arctic relations, while striking a hard line about US rights.

The calm face:

The Arctic region is peaceful, stable, and free of conflict. The United States and its Arctic allies and partners seek to sustain this spirit of trust, cooperation and collaboration, both internationally and domestically.

The hard line:

We will enable our vessels and aircraft to operate, consistent with international law, through, under, and over the airspace and waters of the Arctic, support lawful commerce, achieve a greater awareness of activity in the region, and intelligently evolve our Arctic infrastructure and capabilities, including ice-capable platforms as needed. U.S. security in the Arctic encompasses a broad spectrum of activities, ranging from those supporting safe commercial and scientific operations to national defense.

This assertion of national defense and air and water rights came just two days before the May 15 meeting of the Arctic Council. It was meant to send a message that the US role as an aggressive competitor in the Arctic race would not be hindered by the faltering LOST, an administration priority.

An unlikely alliance advocates for the treaty. It includes oil, gas, mineral, telecommunications, environmental, commerce, trade and business interests. Organizations as divergent as the Natural Resources Defense Council and the US Chamber of Commerce have called for Senate approval. All Secretaries of State dating to President Ronald Reagan say ratifying the Treaty will gain the US a guaranteed, peaceful right to a large swath of the mineral-rich Arctic seabed, the deep oil reserves, and expanding sea lanes.

But the issue of ratification of LOST has upset normally solid alliances in conservative politics, just enough to obstruct Senate ratification. It is opposed by the Heritage Foundation, and has divided Republican Senators, with a key group saying it will undermine American sovereignty, subject the US to the environmental laws of other nations, and interfere with our inherent right to navigate and explore oceans freely.

Senators Rob Portman (R-OH) and Kelly Ayote (R-NH) headlined a July 16, 2012 news release: “Senators Portman and Ayotte Sink Law of the Sea Treaty.” Their votes were necessary to reach the 2/3 majority to ratify the treaty. The release also announced a letter to Senate Majority leader Harry Reid that read in part:

No international organization owns the seas, and we are confident that our country will continue to protect its navigational freedom, valid territorial claims, and other maritime rights.

But Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AL) wrote in a June 8 Op Ed in the Alaska Dispatch:

[T]he Law of the Sea Treaty affords each of the five countries that surround [the Arctic Ocean] an exclusive economic zone out to 200 nautical miles from shore. The natural resources within a nation’s zone belong to that nation alone. Parties to the treaty can also lay claim to an extended area out to 350 nautical miles. If the US Senate were to ratify the treaty – and the US is the only Arctic nation that has not ratified – America could lay claim to an area of the Arctic twice the size of California. Ownership in the Arctic is becoming increasingly important as more and more nations look to the region to meet their energy and economic needs, and as a viable shipping route.

The Obama administration’s continuing failure to achieve treaty ratification has been a bitter one. In a May 23, 2012 hearing before then Senator John Kerry’s Foreign Relations Committee, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton testified:

As the Arctic warms and frees up shipping routes it is more important that we put our navigational rights on a treaty footing and have a larger voice in the interpretation and development of the rules because it won’t just be the five Arctic nations, you will see China, India, Brazil, you name it, all vying for navigational rights and routes through the Arctic.

After a cold reception from key members, Kerry postponed a committee vote to keep it “out of the hurly-burly of presidential politics.” There has been no progress since. He later wrote in Politico:

We’ve dealt ourselves out of the game that’s unfolding right before us. . . [LOST] can strengthen our hand against China and others, which are staking out claims in the Pacific, the Arctic or elsewhere. It is designed to give our oil and gas companies the certainty they need to make crucial investments to secure our energy future. It puts our telecommunications companies on equal footing with foreign competitors. And it will help secure access to rare earth minerals, which we need for computers, cellphones and weapons systems that allow us to live and work day in and day out.

The current position of the Obama administration, now with Kerry as Secretary of State, is no less adamant. The focus is firmly on economic development. It could have been written by the US Chamber of Commerce, which said of LOST:

The treaty provides certainty in accessing resources in the Arctic and Antarctic and could ultimately enable American businesses to explore the vast natural resources contained in the seabeds in those areas.

The persistent drumbeat on economic exploitation of the Arctic by the US and other Arctic nations has rightfully worried environmentalists. When China, India, Italy, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea were admitted as observers to the Arctic Council last May, worry escalated that “a paradigm shift in geopolitics is taking place in the region,” according to Yale ‘s Environment 360. China has significantly stepped up its interest, announcing in June the creation of a China-Nordic Arctic Research Center and convening a conference in Shanghai on “China-Nordic Cooperation for Sustainable Development in the Arctic: Human Activity and Environmental Change.”

Economic development almost always trumps environmental policy these days, and the Arctic, for all its romance and images of pristine nature, is no exception.

Vagueness about environmental policy is a consistent thread throughout the plans of nations with Arctic interests. Details are certainly absent from the White House strategy. While the US rhetoric may be effective on national defense and navigation rights, it reads like tired, naive platitudes when applied to the environment:

Responsible stewardship requires active conservation of resources, balanced management, and the application of scientific and traditional knowledge of physical and living environments. As Arctic environments change, increased human activity demands precaution, as well as greater knowledge to inform responsible decisions. Together, Arctic nations can responsibly meet new demands – including maintaining open sea lanes for global commerce and scientific research, charting and mapping, providing search-and- rescue services, and developing capabilities to prevent, contain, and respond to oil spills and accidents.

Defenders of Wildlife explains a major spill in the Arctic Ocean would cause unavoidable catastrophic consequences:

Conditions in the Arctic are extreme, making the hope of a timely or adequate response to an oil spill unrealistic. The ocean is completely iced over for much of the year. In the summer, week-long storms and 20-foot seas with gale-force winds and thick fog are common. In addition to endangering the lives of cleanup crews, these conditions are likely to render response technology useless—oil booms can’t be deployed or won’t work in stormy seas; skimmer boats and equipment are similarly unusable.

Commercial fishing in the Arctic is also a concern. A FAQ created by The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Oceans North International campaign describes the threats that would be posed by international fleets to a newly opened Central Arctic Ocean, 92% of which has no regulations or international agreements governing fishing. Add the profound disturbances associated with mining the ocean floor, the potential damage caused by regular shipping, and the complexities of joint governance by more than a dozen, sometimes mutually hostile, nations. The environmental future of the Arctic is assuredly in question.

Economic development almost always trumps environmental policy these days, and the Arctic, for all its romance and images of pristine nature, is no exception. Emblematic was Hillary Clinton’s appearance before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee last year. Senator Bob Corker (R-TN) expressed concern that LOST may obligate the US to reduce carbon emissions. She assured him that the treaty would do no such thing and took pains to list the ways it would be “no backdoor Kyoto Protocol.”

There is nothing in the convention that commits the United States to implement any commitment on greenhouse gasses under any regime. And it contains no obligations to implement any particular climate change policies. It doesn’t require adherence to any specific emission policies.

The irony is painful.