Dr. Francis Marchese is Professor of Computer Science at Pace University’s Seidenberg School of Computer Science and Information Systems, and a Faculty Scholar with the Pace Academy for Applied Environmental Studies. Find more information about Dr. Marchese here.

Superfund 365 is a tour de force of data visualization design, artist-scientist collaboration and political subversion. Created by artist Brooke Singer to capture the 365 worst Superfund sites, one day at a time, from September 1, 2007 through August 31, 2008, the website exposes the complexity of the nation’s toxic waste problem to a general audience. Though its one-year run is over, the site is a graphic example of how the digital arts can elucidate and inform, and remains an accessible, on-line archive ripe for exploration and personal commentary.

The term Superfund is probably unknown to most Americans in their 30’s or younger. For the rest of us, it likely evokes images of Love Canal, a neighborhood in the LaSalle area of Niagara Falls, NY, that was built atop 20,000 tons of toxic waste, or the Valley of the Drums in Bullitt County, Kentucky, where thousands of drums of industrial wastes were buried on one 23 acre site. In response to growing concerns about toxic sites, their threat to human health, and the cost of cleaning them, Congress enacted the 1980 Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act(CERCLA), or the Superfund Law, as it is more commonly known.

The Hudson River, contaminated for decades with toxic waste from the General Electric manufactruing plants along its banks, is the longest Superfund hazardous waste site in the United States, stretching for over 40 miles. Image credit: NASA, Christopher G. Reuther/EHP, as presented on Superfund 365.

One of the more famous Superfund sites in the nation is the General Electric PCB site on the Hudson River, EarthDesk’s home river.

Superfund created a process for identifying sites, established a National Priorities List (NPL), and implemented a trust fund — a Superfund — to assure clean ups could be paid for. It also empowered the Environmental Protection Agency to compel responsible parties to perform cleanups or to reimburse the government for cleanups conducted by the EPA. Unfortunately, the petroleum industry tax, which originally funded the program, ended in 1995, and funding by Congress cannot keep pace with the cost of cleaning up hazardous sites. There is more information from EPA on Superfund, its history, status and funding here.

Brooke Singer’s goal in creating Superfund 365 was to transform the dense text of CERCLA’s Superfund webpages and database into a visually engaging and useful environment that encouraged exploration. The challenge that she and her workers faced was to piece together EPA data that was at times complex, inconsistent, inaccurate, and inhomogeneous.

In addition to the NPL, they employed the Center for Public Integrity’s list of the Most Dangerous Superfund Sites, as an aid in organizing and prioritizing this data. They narrowed their list to 365 sites by eliminating sites where data was inconclusive and sites that were no longer on the NPL. Next, they plotted selected sites on a map, and planned a cross-country trek of Superfund site visits beginning in the New York City area, working across cross country, finally ending the year at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii.

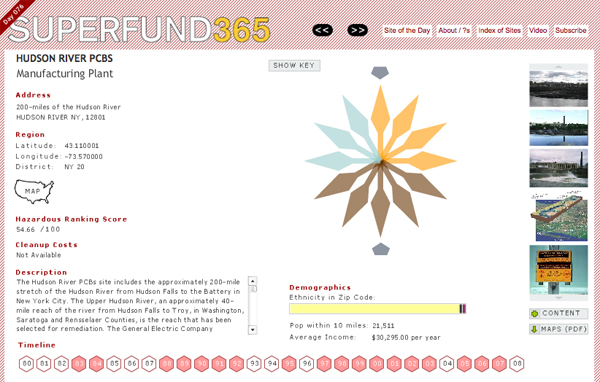

Superfund 365 exhibits a clean visual schema that integrates essential text about a site (e.g. location, brief description, and clean-up costs) with simple graphics for data representation:

A pinwheel graph displays contaminants, surrounded by pointers representing the entities responsible for their presence. When a mouse is placed over a pointer, a popup exposes the type of contaminant. Executing a mouse click on a pointer launches a descriptive webpage from the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) for that substance. A timeline across the bottom of each page displays actions taken for the featured site. And a horizontal bar chart highlights the ethnicity distribution in the site’s zip code, annotated with the population within ten miles and the average income in the area. Beyond graphical interactions, viewers may engage the website by entering comments and uploading photos.

On a higher plane, Superfund365 positions the audience in relation to environmental threat. Toxic ranking scores, site photos, and demographic descriptions of populations potentially at risk put viewers on the map, making them residents of the places that Dow Chemical, GE, and hundreds more, have ruined. Singer’s work falls naturally within the tradition of politically motivated art that seeks to stimulate debate, and potentially provoke social and political change.

Since Superfund365 was introduced, more sites such as the New York City’s Gowanus Canal and Newtown Creek continue to be added to the Superfund list. Today, Brook Singer has taken to photographing Superfund sites as part of a book project (see Gowanus Canal below) while continuing to practice her art of social activism. At a time when there is increasing public knowledge about chemicals in consumer products, there is decreasing knowledge about the actual environment itself. And with one in four Americans living within four miles of a Superfund site, it is time for a reawakening to environmental issues. A good place to begin is Superfund365.