For five days, 300,000 people of Charleston, West Virginia and the surrounding area lost their regular source of drinking water due to a spill of 4-methylcyclohexane methanol by Freedom Industries into the Elk River. Investigations into the cause are underway.

Alarmed and puzzled residents, government officials, and reporters demanded answers. Among the most asked questions:

Question 1: Is 4-methylcyclohexane methanol toxic?

Question 2: Why is a dangerous industrial chemical being used adjacent a public water supply?

Perplexing questions but the answers are of the everyday, garden variety in the behind-the-scenes debate over regulation of toxic, hazardous and industrial chemicals.

Answer 1: There is no reliable answer. 4-methylcyclohexane methanol, an industrial compound used in coal production, is one of more than 85,000 chemicals for which there has been inadequate testing.

Answer 2: Water supplies all over the nation are in the vicinity of facilities that store, use or transport hazardous and toxic chemicals.

How dangerous is the spill really?

That depends on who’s talking.

Monday on MSNBC’s Daily Rundown, Chuck Todd dismissed the chemical with one bite of sound, “Not deadly.” Have we become so jaded that “deadly” is now the measure of dangerous?

At a January 10 news conference, Jeff McIntyre, president of American Water Company, which supplies the region’s drinking water, said, “I can’t tell you that the water is unsafe, but I also can’t tell you that the water is safe.” It was also reported the water smelled like licorice and tasted bad.

At a January 10 news conference, Jeff McIntyre, president of American Water Company, which supplies the region’s drinking water, said, “I can’t tell you that the water is unsafe, but I also can’t tell you that the water is safe.” It was also reported the water smelled like licorice and tasted bad.

The American Association of Poison Control Centers was so in the dark about 4-methylcyclohexane methanol it actually used McIntyre’s ambivalent observation in a news release.

The Charleston Gazette did the best job of summing up the poor state of information:

“There’s not much known about this chemical,” said Dr. Elizabeth Scharman, longtime director of the West Virginia Poison Center, which has been fielding calls from concerned residents since the emergency began.

“There’s not much known about this chemical,” said Dr. Elizabeth Scharman, longtime director of the West Virginia Poison Center, which has been fielding calls from concerned residents since the emergency began.

What Scharman and toxicologists she’s consulted with are comfortable saying is that the material is likely an “irritant” that could cause itching or burning of eyes, skin and the respiratory tract. It could, in some cases, prompt vomiting or diarrhea.

. . . Still, some emergency response and environmental protection officials have been quick to assure the public that 4-methylcyclohexanemethanol isn’t “hazardous.” They’ve made that statement based on one limited piece of evidence: the fact that it’s not listed as a material whose shipment is regulated by the federal Department of Transportation.

However, the material-safety data sheet, or MSDS, being cited by some of those same officials indicates that the substance is considered hazardous under other regulatory standards, such as those set by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

Particularly puzzling is why, given the possible physical reactions to the chemical, and the Gazette’s citation of OSHA, there was ever a reluctance to warn the public that 4-methylcyclohexane methanol is toxic. Cornell University includes vomiting, diarrhea, itching, and irritation in its definition of acute toxic reactions.

Is it necessary to use 4-methylcyclohexane methanol near a water supply?

Like it or not, facilities such as Freedom Industries are in the tradition of factories that grew near river commerce routes, where it is common to store, use and transport chemicals. Virtually every river or major lake in a populated area in the United States has fuel tank storage, industry, freight rail, a port, or all, often near public water supplies

Decades without serious mishap have instilled a passive acceptance. One accident would shake that up immediately, as it did in Charleston.

Here on EarthDesk‘s home river, the Hudson, tankers, and tugs pushing oil and gasoline barges literally operate right above the water intakes of the City of Poughkeepsie, Town of Lloyd, Villages of Port Ewen and Rhinebeck.

Regularly on the west Hudson shore, and often on the east, CSX railroad transports hazardous freight in tank cars on miles-long stretches of track just feet from the water line. The east rail runs immediately next to the Poughkeepsie water plant.

The large tanks of the Hudson Fuel Terminal in Kingston, NY are located directly across from the drinking water intake at Rhinebeck, and just north of Port Ewen’s. It is one of many.

Decades without a serious mishap have instilled a passive acceptance of these juxtapositions. One accident would shake that up immediately, as it did in Charleston.

Something is broken, what is it?

In short, the law and public attention. The blasé acceptance by the Hudson River Valley public of the daily adjacency of toxic chemicals to drinking water is born of incident-free experience not unlike that of the citizens of Charleston, WV prior to January 9. Multiply that times hundreds of regional populations along developed waterways in the U.S.

But it is also fair for the public to expect that the law provides adequate protection, that dangerous chemicals are routinely regulated, kept at a safe distance from our daily lives and local ecosystems.

Not so.

In the December 19 EarthDesk we wrote:

The larger question of safety is too often answered too late, if at all. The 1976 Federal Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) does not protect the public and the environment from dangerous chemicals.

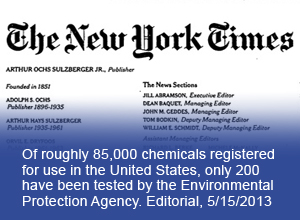

We cited a New York Times April 18 editorial. It is important enough to cite again:

For the most part, the law requires the government to prove that a chemical is unsafe before it can be removed or kept off the market instead of requiring manufacturers to prove that their chemicals are safe before they can be sold and used. And it makes it hard for the Environmental Protection Agency to pry the information it needs to assess risk from the manufacturers or to require them to conduct tests.

Companies have to alert the E.P.A. before introducing new chemicals, but they don’t have to provide any safety data. It is up to the agency to find relevant scientific information elsewhere or use inexact computer modeling to estimate risk. The agency can only ask the company for data or require testing if it first proves there is a potential risk, which is hard to do without the company’s data.

The failure of the law can be read in these dismal statistics: since 1976, from a universe of chemicals that now numbers roughly 85,000, the agency has issued regulations to control only five existing chemicals.

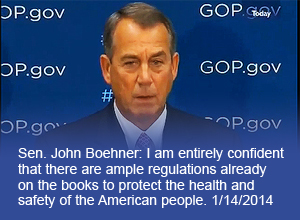

Questioned about the need for new laws or regulation, U.S. Senate Majority Leader John Boehner scoffed:

The issue is this: We have enough regulations on the books. And what the administration ought to be doing is actually doing their jobs . . . I am entirely confident that there are ample regulations already on the books to protect the health and safety of the American people.

Though her bill does not go far enough to guard from another Charleston type incident, New York’s Senator Kirsten Gillibrand offers a step in the right direction with her sponsorship of the Safe Chemicals Act of 2013 (S 696) to reform the Toxic Substances Control Act.

Watch EarthDesk for further updates on the West Virginia spill, and the Safe Chemicals Act.