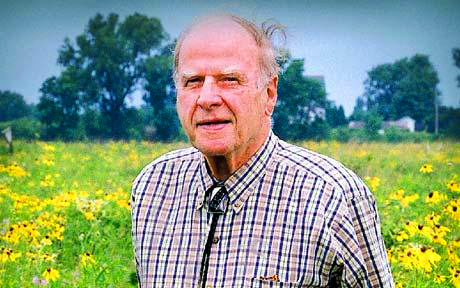

Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, 1916-2005

In 1969, Gaylord Nelson proposed the creation of an Earth Day. He was a United States Senator.

It is hard to picture an elected federal official announcing that bold an initiative today. No, it is impossible.

But so compelling was his proposal, it prompted President Richard Nixon to jump into the fray. Determined to beat Senator Nelson to the punch, the president declared in his first inaugural address on January 22, 1970, “We have incurred a debt to nature and now that debt is being called.” It was the central message of the address, 20% of which was devoted to environmental issues. The New York Times hailed the president’s speech in a front page story.

Senator Nelson, a Democrat, had his chance three months later, to the day. In a speech delivered on April 22, the first Earth Day, he described the environmental cause in passionate language that resonated essential American values:

Our goal is not just an environment of clean air and water and scenic beauty. The objective is an environment of decency, quality and mutual respect for all other human beings and all other living creatures. Our goal is a new American ethic that sets a new standard for progress. . . Are we willing? That is the unanswered question.

In 2013, it is unanswered still.

1970 launched a golden era of American environmentalism, a time when leading senators and representatives, and the president of the United States, were unabashed, boastful even, about their environmental platforms. Imagine that.

President Nixon ushered in the National Environmental Policy Act and used his executive authority to create the Environmental Protection Agency. The decade saw Congress launch the most ambitious body of environmental law on the planet, including the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, Safe Drinking Water Act, Endangered Species Act, Toxic Substances Control Act, Environmental Pesticide Control Act, Coastal Zone Management Act, Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, Marine Mammal Protection Act, and Resource Conservation and Recovery Act. More information on environmental law at the Cornell University Legal Information Institute.

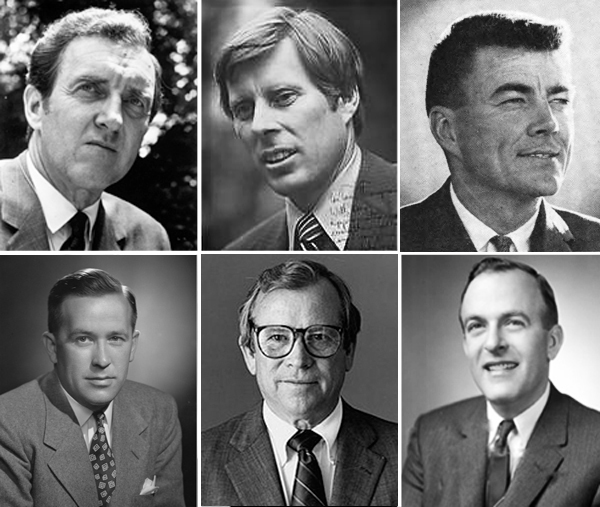

Following this post are photos of some of the federal environmental leaders of the time. They are heroes mostly forgotten. How many can you name? The first reader to name them all wins a book.

Four decades later, the goals of the nation’s environmental laws are largely unattained. From the fracking fields of Pennsylvania to the pollution blighted waters of the Northeast to oil ravaged Nigeria, where the U.S. gobbles 40% that nation’s petroleum, the planet’s environmental challenges are more daunting, the Congress more timid, than anyone thought possible in the 70s. Climate science is a political football. The innovation talent of the private sector has not been enlisted. A new generation of Americans is growing accustomed to environmental degradation.

Consider the 1972 Clean Water Act, our nation’s most ambitious environmental law. In 2013, it is still the goal of the law to end the discharge of pollutants by 1985. We live in a blue nation — not Democratic blue but water blue. America was founded on its shores and rivers. Yet, throughout the country, fisheries are shuttered, 19.5 million Americans are made ill by drinking water annually, and families plan vacation days around beach closures. In a January 10, 2010 internal memorandum to her staff, EPA Administrator Lisa P. Jackson wrote, “America’s waterbodies are imperiled as never before.”

by 1985. We live in a blue nation — not Democratic blue but water blue. America was founded on its shores and rivers. Yet, throughout the country, fisheries are shuttered, 19.5 million Americans are made ill by drinking water annually, and families plan vacation days around beach closures. In a January 10, 2010 internal memorandum to her staff, EPA Administrator Lisa P. Jackson wrote, “America’s waterbodies are imperiled as never before.”

Forty-three years after the first Earth Day, Gaylord Nelson’s question rings prescient still: Where is the will? Largely absent, if the modern Congress is the measure. Most members fear the election day consequences of a meaningful environmental agenda. The legacy of their congressional forebears is ignored. We need a new era of leadership and massive environmental policy reform, which begs the inescapable question: Why did American environmentalism fail to sustain and build upon the political support that launched its modern movement?

How do citizens fit in? Ask your federal representative and senator for a new date to eliminate water pollution. Most will not understand the question. Explain politely. Ask about the last time they read the goals of our four-decade old environmental laws written to protect air, land, oceans, species and end pollution. Ask why America is not leading a worldwide campaign for a sustainable planet, and building a sector of our economy around that enterprise. Take time to learn on your own about the extraordinary goals contained in the landmark environmental statues designed to guarantee today’s children would not face a lifetime of environmental threats.

One role I envision for EarthDesk is a forum that provides a fresh and critical look at the nation’s environmental laws and policies. Taken together, they present a stirring vision for a sustainable environment that is an American right essential to the public welfare, often in language as profound as our founding documents, and built around a moral center with which we have lost touch.

Borrowing again from the late Senator Gaylord Nelson, in his 1995 speech on the 25th anniversary of Earth Day:

A monumental moral cause is near at hand and a far more serious challenge than the Cold War ever was. It’s the war against the planet. How do we bring it to an end and where do we start? It must start in the United States. We cannot and should not wait for the rest of the world.

How many environmental heroes can you identify? Be the first to name them all and win a book.