Who Is David Bernhardt? (And Why Every Environmentalist Should Care.)

The man who’s likely to replace Ryan Zinke as Interior secretary is a seasoned Washington insider—and (surprise!) a former lobbyist for Big Oil and Big Ag.

Ed. Note: Jeff Turrentine is the Culture & Politics columnist for onEarth, a digital publication of the Natural Resources Defense Council. The article below is excerpted from Jeff’s profile of David Bernhardt in the November 14 edition. ~ JC

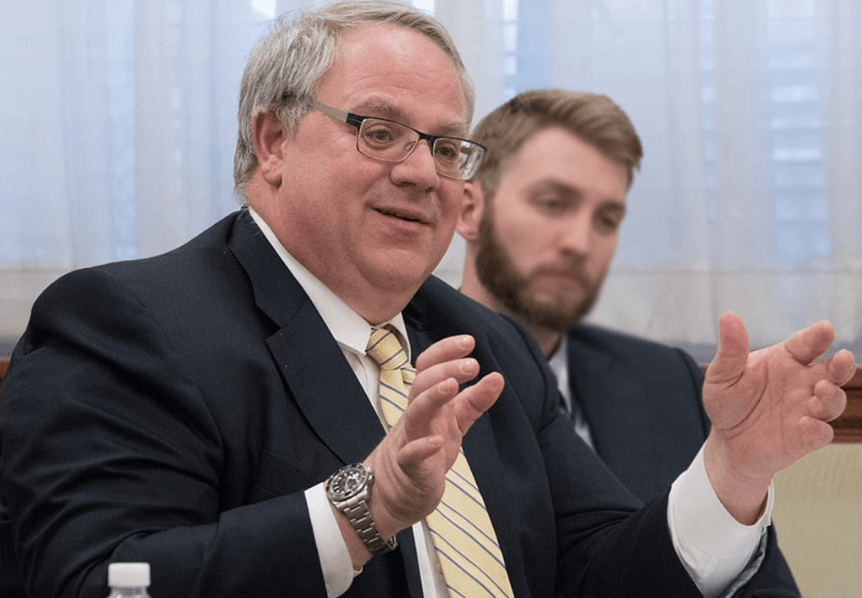

Meet David Bernhardt, the Interior Department’s current deputy secretary, whose long Washington résumé suggests that he would happily continue to carry out the Trump administration’s war on public lands and federal waters—albeit with greater legal sophistication and fewer unforced ethical errors than his predecessor.

Like [Zinke], Bernhardt grew up in the mountain West: in his case, Colorado’s Western Slope. Unlike Zinke, who spent more than 20 years as a Navy SEAL before winning Montana’s sole congressional seat in 2014, Bernhardt has been in Washington for nearly two decades, having first joined the Interior Department back in 2001 as deputy chief of staff to then-Secretary Gale Norton. Five years later, President George W. Bush named Bernhardt solicitor for the agency, a job that had him overseeing the legal staff that represents the department in court cases and directing its overall legal strategy. During this first go-round at the agency, Bernhardt worked to open up Yellowstone National Park to recreational snowmobilers and the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas development.

When the Obama administration came to town in 2009, the winds of change sent Bernhardt spinning through the Washington revolving door that deposits outgoing top-tier political staff into positions at D.C.’s most powerful lobbying firms. (This door, in case you were wondering, is located in the proverbial swamp.) He spent the next seven years as a registered lobbyist whose clients included Samson Resources, the largest privately held crude oil and natural gas company in the United States; Halliburton, the multinational oilfield services company where former vice president Dick Cheney once was CEO; Rosemont Copper, a proposed copper mine near Tucson that’s been the subject of an 11-year legal battle with Native American tribes and environmental groups; and the Independent Petroleum Association of America, a consortium made up of thousands of oil and gas producers scattered across the country.

Bernhardt’s client list was heavy on fossil fuel interests, but one of his biggest lobbying jobs was for the Westlands Water District, the largest agricultural water district in the country and the chief provider of water to farmers in California’s Central Valley. After rejoining Interior last year as its deputy secretary, Bernhardt became Zinke’s point man on an agency-led plan for “maximizing water supply deliveries” to the Central Valley—even if such efforts were found to violate wildlife protections under the Endangered Species Act. Westlands strongly supports such a plan, a fact that has already raised questions about Bernhardt’s independence from his former client. Last year the Campaign for Accountability, a good-government watchdog group, sent a highly detailed letter to the U.S. Attorney’s office, urging it to investigate whether Bernhardt “has continued to lobby despite formally withdrawing his registration in 2016.”

If Bernhardt is worried about conflicts of interest or the appearance thereof, he’s certainly not letting on. In August he penned an op-ed for the Washington Post painting the Trump administration’s dreadful proposal to weaken protections for threatened wildlife as a means of bringing the Endangered Species Act “up to date.” The changes he has in mind could very well result in the ceding of critical wildlife habitat to corporate interests.

Such as regional water districts, for example. Or perhaps oil and gas companies. Or maybe copper mines.

Secretary Zinke had a plan to shrink and sell off our public lands to the highest bidder, and he was actually making good on that plan until his own penchant for penny-ante corruption got in the way. But if Americans think they’ll be getting a better secretary of the Interior once Zinke’s out, they’re sadly mistaken. They’ll just be getting a shrewder one.

«« »»