On the Hudson

The Shad Returned. Fishermen Didn’t

Lost is the personal evocation of a river few will ever know.

“A day comes to the banks of the Hudson when the sun shines, small white clouds ride on soft air blowing steadily upriver and the silver-backed shad are running. Then from the shadow of Manhattan’s towering uptown apartments to the shacks on the pebbled shores above Kingston men in weathered clothes turn weathered faces to the water.” ~ Carl Carmer, The Hudson, 1939

« « » »

The life history of the American shad is a remarkable piece of ecological choreography. This largest member of the herring family spends the year swimming a round-trip circuit between Florida and Canada following the isotherms of the warming then cooling Atlantic waters. On their journey north, schools of adults break-off to spawn in their rivers of origin – such as the St. John’s in December, the Hudson in late March and the St. Lawrence in July.

In the fresh water reaches females lay their eggs in sandy and gravelly bottoms. Fertilized eggs and hatched larvae are carried progressively downriver with the flooding and receding tides. When able, the young swim for the ocean, maturing and growing heartier in the increasingly brackish and nutrient-rich estuarine ecosystem. After four to five years, and as much as 10,000 miles at sea, the now adult shad are ready for their return home, where they will repeat the spawning rite of generations of forbears. [ASMFC; Limburg, et al]

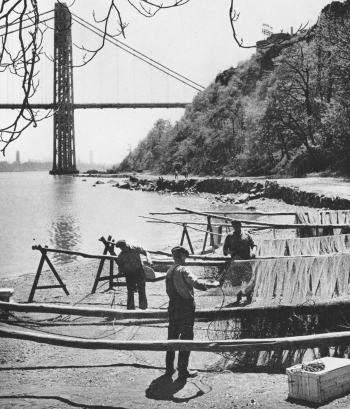

Preparing nets near the George Washington Bridge, 1946

On the Hudson, and all Atlantic coastal rivers, the invisible arrival of shad was announced by the appearance of commercial fishermen, or rivermen — a certain sign spring had come. No longer. Hidden beneath the scores of environmental victories that led to the Hudson’s celebrated renaissance is the failure to protect its commercial fishing industry from collapse.

Like the first chorus of peepers and the flowering forsythia, the return of Hudson rivermen to work the annual shad run was a biological event that once signaled the season. Where a local waterfront gave enough way to the river, tools of the fishery were in evidence: 18-foot skiffs beached and outfitted; nets racked for repair and deployment; 50-foot hickory poles for driving into the river bottom to hold fast the nets; piles of line, anchors, floats and crates; fishing shanties that squatted on shore — thanks to the handshake of a land owner or blind-eye turned by a town.

The rivermen’s industry dates to the Dutch settlers who likely learned from native American Indians. [Hotala] Generations of fishers bequeathed to their successors a working knowledge of the river that bests any scientist or government official. Their understanding of the habitats, behavior and movement of a variety of species enabled many to fish year-round, even when ice choked the shores and channel.

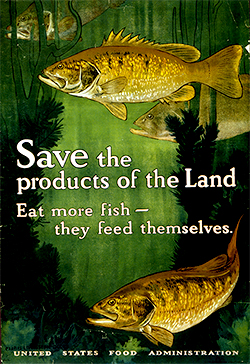

During hard times the Hudson River fishery was an economic safety net that lent needed work, and a ready food supply. The late Gus Zahn, a riverman from Poughkeepsie, recalled to me in 1981 that during World War II federal officials came to the DeLaval factory, his workplace, seeking those who knew how to fish the Hudson. His recollection was reminiscent of a federal initiative during World War I when the United States Food Administration published a poster that read, “Save the products of the land. Eat more fish — they feed themselves.” The work and traditions of rivermen were integral to Hudson Valley and American culture, as romanced in Harper’s Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, The Illustrated London News, National Geographic, Joseph Mitchell’s Bottom of the Harbor, Robert H. Boyle’s The Hudson River: A Natural and Unnatural History, and Carl Carmer’s The Hudson, his contribution to the Rivers of America book series.

During hard times the Hudson River fishery was an economic safety net that lent needed work, and a ready food supply. The late Gus Zahn, a riverman from Poughkeepsie, recalled to me in 1981 that during World War II federal officials came to the DeLaval factory, his workplace, seeking those who knew how to fish the Hudson. His recollection was reminiscent of a federal initiative during World War I when the United States Food Administration published a poster that read, “Save the products of the land. Eat more fish — they feed themselves.” The work and traditions of rivermen were integral to Hudson Valley and American culture, as romanced in Harper’s Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, The Illustrated London News, National Geographic, Joseph Mitchell’s Bottom of the Harbor, Robert H. Boyle’s The Hudson River: A Natural and Unnatural History, and Carl Carmer’s The Hudson, his contribution to the Rivers of America book series.

On March 18, 2010, New York State effectively ended what remained of the Hudson commercial fishing industry when it implemented a ban on shad fishing due to crashing populations. [NYSDEC] It was the culmination of a slow-motion death march that had its start 35 years earlier when Commissioner Ogden Reid of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation acknowledged to New York Times reporter Richard Severo that the river’s striped bass were contaminated with polychlorinated biphenyl, or PCB, a suspected human carcinogen. [Severo Aug] That announcement on August 18, 1975 was one in a series of devastating revelations — including the valley of the drums in Kentucky, kepone contamination of the James River in Virginia, and Love Canal in the Niagara frontier of upstate New York — that introduced the toxic age to the United States in the 1970s.

Rivermen and striped bass, Garrison, NY, ca 1950. (Photo found in a dumpster in Peekskill, NY in 2010)

The Times headline labeled Hudson stripers a “toxic peril.” To explain in 1975 why the generally unknown compound PCB would have such an effect was to speak a foreign tongue — an invisible, odorless, chlorinated hydrocarbon poisonous in such minute amounts it contaminated 200 miles of river.

As startling was the revelation that two General Electric factories in Fort Edward and Hudson Falls, NY were the cause of the contamination, and that discharges from the plants had been known since 1946. Overnight, environmental organizations that boasted of their role in the Hudson’s miracle recovery had to retrench for a rearguard battle they did not yet understand.

On October 17, 1975, Commissioner Reid traveled by helicopter to Claverack, Poughkeepsie, Garrison and Verplanck to tell rivermen his department was investigating all commercial species for a possible prohibition on sale. [Severo, Oct. 1975] At a follow-up meeting on February 17, 1976, he told them he would issue a ruling within a week. [Severo, Feb. 1976] It was important to Reid to conduct the meetings personally. These rare acts of consideration earned the commissioner the rivermen’s trust, at least initially.

Reid asked the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association for an emissary who could travel to individual fishing camps and relay the ruling immediately upon its enactment. I volunteered. One week later, Reid called me at my home in Clintondale, New York at 9 AM sharp to provide the details. On speaker phone with the commissioner was his general counsel and deputy commissioner for fish and wildlife. The ruling, he explained, included a ban on striped bass, catfish, perch, and Atlantic sturgeon under four feet in length. I inquired about American eel. The deputy said that the department had yet to decide if eel are a fish or snake. Before I could suggest politely that they consult a dictionary, the department’s chief biologist entered the room. He hurriedly corrected the others present, saying American eel are indeed fish, and that they too were banned. Fishing for American shad, adult Atlantic sturgeon and blue crab were still allowed. Because shad and adult sturgeon spend most of their lives in the ocean they do not concentrate impermissible levels of the oil-soluble PCB in their fatty tissue. Blue crab meat is virtually devoid of fat.

John Cronin and Henry Gourdine of Ossining build a shad boat. Lisa Weiss, 1981

With dread, I made my stops up and down the valley to deliver the news. The expression “way of life” can be overused, but it well defined the gravity of the ruin. The reactions of Rivermen ranged from silent incredulity to loud anger; some choked on their emotions. Many were multi-generational, by family or family friend. Bob Gabrielson of Nyack owned and operated Gabrielson Fisheries with sons Robert and Eric. Son of a lobsterman, he inherited his operation alongside the Tappan Zee Bridge from the riverman who taught him the business. The DeGroats of Stony Point traced their fishing roots through so many generations of Dutch they had lost track. Everett Nack of Claverack taught his sons to seine as soon as they could stand; by their teens they could direct the family fishing operation. [Nixon, Cronin]

For the most part, the rivermen’s rage was reserved for the state. They could not reconcile that PCBs were dangerous enough to shut down their business, but safe enough to allow GE to discharge for three decades. The ruling was doubly bruising for “men who, in some instances, had spent their lives fighting for a cleaner river, only to learn what appeared to be clean contained a chemical they had never heard of,” as Times reporter Severo wrote. [Severo, Oct. 1975] Administrative law judge Abraham Sofaer later blamed “regulatory failure” and “corporate abuse” for the river-wide contamination. [Sofaer]

The prohibition on bass and eel wrenched the economic heart out of the fishery. Both had brought a premium in the coastal market for years – one dollar to the riverman per pound of eel, twice and more for bass. Over time, many rivermen of the lower Hudson, such as the DeGroat family, had come to identify themselves as striper fishermen above all else. In the upper river, eel fisherman Ivar Anderson of Red Hook didn’t even ship to market; buyers from Boston came to his dock with a live tank to retrieve the catch.

Shad, sturgeon and crab were not near as lucrative. Fishmongers in the Fulton Market sometimes dropped the buying price for shad to $.30 per pound at the peak of season, the same they paid fishermen in the 1940s. When that happened, rivermen often reduced the amount of net they fished, and some temporarily halted all fishing in the hope of boosting the market price. The catch of sturgeon and blue crab were unreliable year-to-year. And even in a good season the demand for Hudson crab was local and limited because Chesapeake crab dominated the Atlantic marketplace. On March 18, 1976, The New York Times ran a headline no fisherman wants to see: “State May Find Fishermen Jobs.” The state didn’t.

Robert Gabrielson and John Cronin haul shad nets on the Tappan Zee. Lisa Weiss, 1980

The late 1970s into the early 1980s brought peak years for the shad run. In 1981, I worked for Gabrielson Fisheries. That season we had to remove half of our nets when the market, flooded with shad, took a nose dive. Sadly, fresh bad news awaited in the years ahead — a progressive decline in Atlantic coast populations of American shad and Atlantic sturgeon. In 1996, New York State closed the Hudson’s sturgeon fishery due to plummeting numbers coast-wide. Two years later, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) declared a 40-year moratorium on sturgeon fishing. In 2010, came the closure of the shad fishery. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Interior declared Atlantic sturgeon endangered.[NYSDEC Sturgeon]

The ASMFC laid blame for the coastal decline on familiar causes — “overfishing, pollution and habitat loss due to dam construction.” [ASMFC] But those offer no insights about the Hudson. There had been no new dam construction in the spawning range of Hudson shad, and no evidence of increased pollution. The agency did not identify specific culprits, such as power plants. These massive illegal fishers, such as the Indian Point nuclear plants, have not been the bailiwick of management agencies, due to regulatory controversies over cooling water intakes at EPA. Power plants on the Hudson could kill as much as 50% of the river’s shad at all life stages in the course of a given year, up to and beyond the time of the shad crash. [NYSDEC DEIS] There is no credible evidence that fishing by Hudson Rivermen contributed to the shad’s decline. Nonetheless, in its 2009 review of the status and history of the fishery, New York State declared that limiting commercial fishing “is the only cause that managers can control” [Hotala] — a statement that must have brought great relief to power plant owners.

Old time rivermen used to say there are distinct runs of shad, timed to certain flowering plants on shore. Following the forsythia run is the dogwood run – fish a bit larger, with abundant females outnumbering the males. Next comes the lilac shad — the final run and the largest fish of all, repeat spawners especially heavy with eggs. Their reproductive duty met, those that survive leave the river to rejoin the continuing Atlantic migration cycle, until they return once again to the river’s freshwater reaches. Eventually, American shad will re-establish itself as a sustainable, functioning population. There is no such hope for Hudson rivermen.

Shad fishermen, Peekskill, NY. Source unknown, ca 1930. (Photo found in a dumpster in Peekskill, NY in 2010)

In a New York Times Op Ed on April 18, 1981, I wrote that in 1976 Commissioner Reid promised “that the PCB problem would not be the death knell of the Hudson’s commercial fishing industry. Angry and shaken, the fishermen nevertheless took the promises in good faith.” [Cronin J.J.] At the time, I was the business agent for the New York State Commercial Fishermen’s Association, in addition to my fishing job with Gabrielson. The rivermen I represented little suspected that the PCB scandal of 1975 would prove to be the opening salvo in a decades-long dismantling of their industry.

Today, the rivermen’s trade is all but gone, with the exception of a small number of die-hard crabbers, and those who net menhaden to bait their crab traps. The contemporary politics of fisheries management and environmental enforcement make it a virtual impossibility the industry will be allowed to revive. “Putting commercial fishermen out of business is a tremendous blow to the river because it destroys the basic, personal ecological constituency that the river has,” said the late Robert H. Boyle, celebrated author, activist and former president of the Hudson River Fisherman’s Association. [Nixon, Cronin]

Forsythia petals are falling. Dogwood are budding. Soon, the perfumed lilac will bloom. Turk DeGroat, Bob Gabrielson, Everett Nack and Gus Zahn have passed away, as have many others. The children of rivermen long ago gave up hope on the family trade, understandably so. Departed with them is the ecological memory that connects communities to the Hudson and the sea. Lost is the personal evocation of a river few will ever know, as Joseph Mitchell captured in “The Rivermen” chapter of Bottom of the Harbor:

A riverman not only works on the river or kills a lot of time on it or near it, he is also emotionally attached to it—he can’t stay away from it. . . Some men work full time on the river—on ferries, tugs, or barges—and are not considered rivermen; they are simply men who work on the river. Other men work only a part of the year on the river and make only a part of their living there but are considered rivermen.

And Carl Carmer, in “The Silversides are Running” chapter of The Hudson:

“Nothin’ prettier than shad scales in the moonlight,” said Henry. “They shine like the blue lamps you see in theaters sometimes. And it’s nice to watch the lights of the houses on the banks go out and then come on again early in the morning.”

And, finally, my friend and former boss, the late Bob Gabrielson, in The Last Rivermen, a documentary I wrote and co-produced with director Robert Nixon. I Interviewed Bob in 1991 when shad fishing was still allowed. The clip below begins with a radio exchange between Bob and son Robert, my former fishing partner, working the one boat they had fishing. In better days, three boats with six crew would have been on the nets. In Robert’s boat was 400 pounds of shad, one-third of a night’s total catch in a usual season. Bob believed his fishing days were numbered:

In an upcoming article, the role of the federal and state government in the demise of the Hudson River’s commercial fishing industry.

« « » »

Sources

- ASMFC, American Shad, A.S.M.F. Commission, Editor. p. 7 – 35.

- Limburg, K.E., K. Hattala, and A. Kahnle. American shad in its native range. in Biodiversity, Status, and Conservation of the World’s Shads. 2003. American Fisheries Society.

- Shad Fishing, in Harper’s Weekly May 1984. p. 412, 423.

- Winter Scene FIshing on the Hudson, in Franke Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. February 13, 1869.

- American Sketches; Shad-fishing on the Hudson, in The Illustrated London News. August 7, 1875.

- Martin, D.B. and L. Marden, Shad in the Shadow of Skyscrapers, in National Geographic. March 1947.

- Mitchell, J., Bottom of the Harbor. 1959, 2008, New York: Pantheon Books.

- Boyle, R.H., The Hudson River: A Natural and Unnatural History. 1969, New York: Norton and Company.

- Carmer, C., The Hudson Rivers of America, ed. C. Carmer. 1939, New York Farrar and Rinehart.

- NYSDEC. Herrings. n.d.; Available from: https://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/7043.html.

- Severo, R., State Says Some Striped Bass And Salmon Pose a Toxic Peril, in The New York Times. August 8, 1975. p. 1.

- Severo, R., Reid Visits Fishermen on the Hudson And Warns Them of PCB Pollution, in The New York Times. October 18, 1975. p. 33.

- Severo, R., Reid to Bar Hudson Fishing, in The New York Times. February 18, 1975. p. 1.

- Nixon, R. and J. Cronin, The Last Rivermen. 1991.

- Sofaer, A.D., Interim Opinion and Order In the Matter of Alleged Violations of Sections 17-0501, 17-0511, and 11-0503 of Environmental Conservation Law of the State of New York by General Electric Company. State of New York Department of Environmental Conservation S.o.N.Y.D.o.E. Conservation, Editor. 1976.

- NYSDEC. Atlantic Sturgeon. n.d.; Available from: http://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/37121.html.

- NYSDEC, Draft Environmental Impact Statement for State Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Permits for Bowline Point, Indian Point 2&3, and Roseton Steam Electric Generating Stations. Table V-26. December 1999.

- Hattala, K.A. and A.W. Kahnle, Status of the Hudson River, New York American Shad Stock NYSDEC, Editor.

- Cronin, J., There Was Once a Time: Shad, Fishermen & the Hudson, J. Cronin, Editor. April 6, 2014: EarthDesk.org.

- Cronin, J., Forsythia are in Bloom; Shad are on the Run. March 29, 2016: BIRE.org.

- Cronin, J.J., The Hudson’s Fishermen, in The New York Times. April 18, 1981. p. A19.