Many are calling tonight’s full moon a “super moon.” More important, it is a Sturgeon Moon, as occurs each August. In honor of its appearance coinciding with EarthDesk Sunday, below is a reprise of last year’s post about the same occasion.

Earlier this evening, I laid my tools on the cabin top of the boat on which I was working, and settled-in to watch the rust red moon crawl to the shoulders of the Hudson Highlands. Once there, it continued upward, as if loosened from the grip of gravity, and floated beyond the river’s cragged peaks.

Earlier this evening, I laid my tools on the cabin top of the boat on which I was working, and settled-in to watch the rust red moon crawl to the shoulders of the Hudson Highlands. Once there, it continued upward, as if loosened from the grip of gravity, and floated beyond the river’s cragged peaks.

It was a Sturgeon Moon. According to the Farmer’s Almanac:

The fishing tribes are given credit for the naming of this Moon, since sturgeon, a large fish of the Great Lakes and other major bodies of water, were most readily caught during [August]. A few tribes knew it as the Full Red Moon because, as the Moon rises, it appears reddish through any sultry haze. It was also called the Green Corn Moon or Grain Moon.

River, mountain, moon, boat; there was no place I would rather have been, except perhaps parked on Bob Gabrielson’s Burd Street Dock in Nyack, NY, of an early May morning in 1981. That day, I climbed out of my pickup truck camper to breakfast on blackfish and watch the red sun rise one hour prior to our fishing tide. Just four weeks earlier, I had resigned my job in the state legislature, moved into the old black Ford, and driven south to join Bob’s commercial fishing crew for the full shad season.

It was a dry spring. Because of the increased salt in the estuary, all manner of ocean fish were making their way into the lower river. In addition to blackfish, we regularly saw flounder, sea robin, starfish, and jellyfish. The previous evening, we picked up a young Atlantic sturgeon, about ten inches in length. A rubber band was wrapped around its midsection, an uncommon but known phenomenon on the river. I would see it again on a different baby sturgeon two summers later off Garrison, NY.

Just beneath the band, the sturgeon’s body was severely constricted and the flesh raw. If the rubber band did not kill it first, its young midsection was now a certain target for deadly infection and fungus. At some point in its short life, the fish had swum into the carelessly tossed band, which became caught on the rough-skinned body and remained while the sturgeon grew.

Sturgeon are a lens into the past. They are often called living dinosaurs. Their lineage dates back 200 million years. In late spring, adult Atlantic sturgeon leave their ocean home to migrate up the Hudson, and other East Coast rivers, to spawn in the freshwater reaches. Young sturgeon use the estuary’s nourishing waters as a nursery ground until they are about three-feet long and hearty enough to begin a life at sea. (Read more here)

Author Robert H. Boyle described sturgeon well in his book The Hudson River: A Natural and Unnatural History:

They have long, leathery snouts on the front of the head, while the bottom part is soft and white with a vacuum cleaner–type mouth that can hang down like the sleeve on an old coat. The eyes are small and glistening, like threatening peas, and the hard body is almost crocodilian, armed with five longitudinal rows of sharp shields, or scutes.

There are twenty-six subspecies of sturgeon worldwide, all with similar physical characteristics, all imperiled.

Just a few miles from our nets, on the Piermont waterfront, Cornetta’s Seafood Restaurant boasted a sight found at no other eatery in the Hudson Valley. Mounted on the wall of the upper dining room was a seven-foot, ten-inch Atlantic sturgeon. When alive, it probably weighed 250 pounds.

“There isn’t a person who doesn’t say, ‘I can’t believe this is out of this river,’” proprietor Suren Kilerciyan once told me. “And they all call it ugly— until they learn that sturgeon is where caviar comes from, and then they change their minds.”

It was by no means the largest sturgeon ever caught. The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats reports a documented female beluga sturgeon captured in the Volga estuary in 1827 that weighed 3,250 pounds and measured twenty-four feet long. According to Boyle, the largest Hudson River sturgeon reached 13 feet.

Its natural history would be the sturgeon’s most remarkable aspect were it not for its stunning decline. Only shark and humans prey on sturgeon. Guess which has decimated the population. Overharvesting of its meat and caviar, pollution, habitat alteration, power plant intakes — the list of insults that humans have invented trump every challenge thrown in the sturgeon’s path during 2,000,000 centuries of life on Earth. In 1996, Atlantic surgeon were banned for capture on the Hudson River, and in 2009 declared endangered, after an unbroken chain of fishing seasons dating back to the same indigenous tribes who honored the Sturgeon Moon.

Imagine those millennia as a twenty-four-hour clock; it has taken us less than one -tenth of a second to endanger all twenty-six subspecies of this enduring, prehistoric fish worldwide. Worth remembering the next time someone passes you the caviar, or you think to cast off a rubber band.

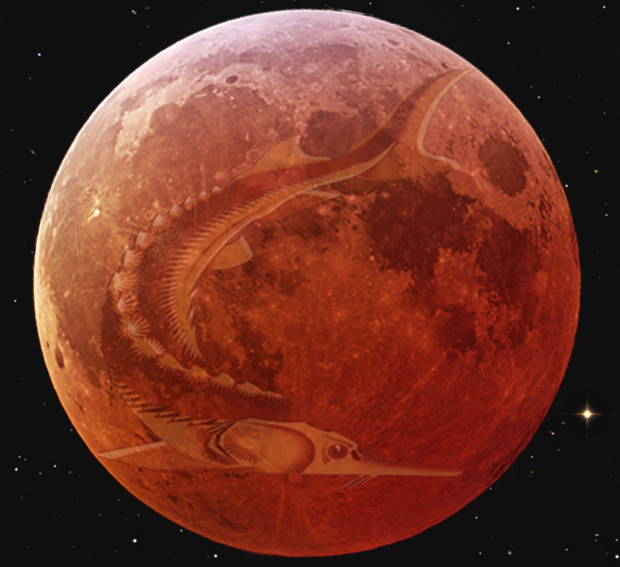

This is a completely fabulous image of the Sturgeon Moon.

I would like to possibly use this orange moon sturgeon image for a new band. I would love to discuss licensing, etc.

Feel free to contact me anytime, 503-209-9673.

Best,

Rod Meyer

Portland, OR