Today is an inauspicious occasion in American environmental history — the thirtieth anniversary of the Federal Clean Water Act’s failure to meet its July 1, 1983 policy goal of “water quality which provides for the protection and propagation of fish,  shellfish, and wildlife and provides for recreation in and on the water.”

shellfish, and wildlife and provides for recreation in and on the water.”

The so-called “fishable-swimmable” standard is no ordinary failure. It is a spectacular failure. The best evidence is the accumulating data about toxic contaminants in fish. Nationally, the number of public health advisories about fish consumption rose from 4,249 to 4,598, or by 8%, between 2008 and 2010, the most recent years for which the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has made statistics available. According to the EPA fish advisory website:

Approximately 17.7 million lake acres and 1.3 million river miles were under advisory in 2010, representing 42 percent of the nation’s total lake acreage and 36 percent of the nation’s total river miles.

And even these numbers are conservative because the EPA listings do not necessarily include state listings. For example, in Minnesota alone more than 1,000 water bodies have warnings. And the State of New York has a general standing advisory that “people can eat up to four one-half pound meals a month (which should be spaced out to about a meal a week) of fish from New York State fresh waters and some marine waters near the mouth of the Hudson River.”

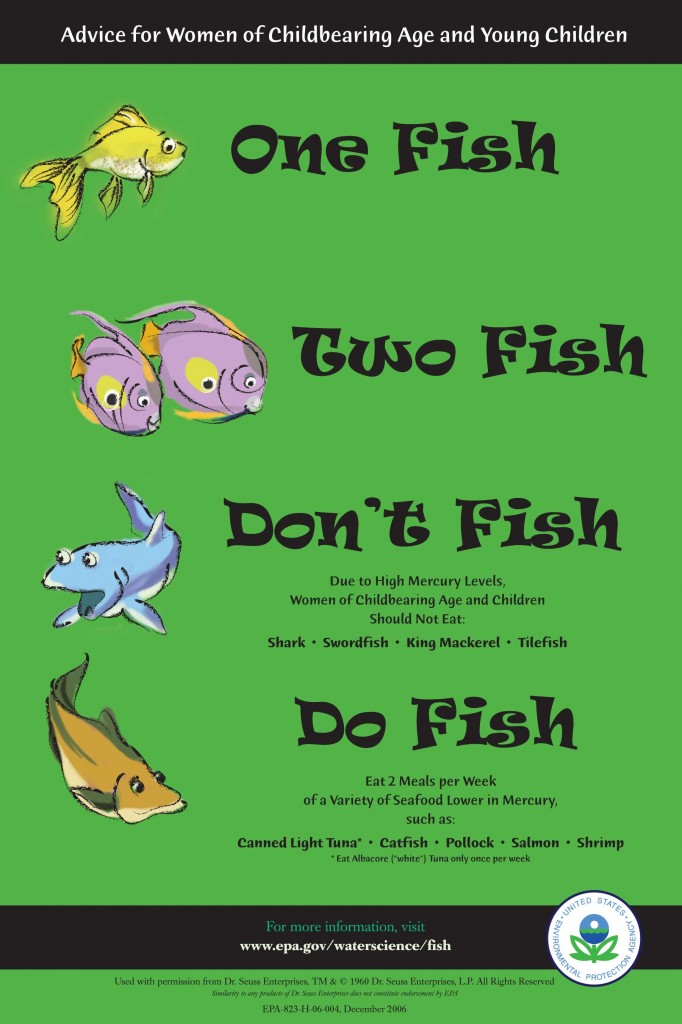

The bad news about fish has been building for decades. (See the gallery at the end of this post). And when fish are poisoned, so too are the wildlife that feed on them, as the mounting problem of mercury contamination testifies. Nationwide, public awareness programs about the dangers of contaminated species, such as the “Fish Smart” campaign on San Francisco Bay, have become commonplace. A sure sign that society has begun to institutionalize this horrifying reality is the now soldout Dr. Seuss collectible poster created by EPA to delight women of child-bearing age and young children with the bad news about “One fish, Two fish, Don’t fish, Do fish.”

On the swimming front, the news from EPA is no better. 40% of the nation’s coastal beaches experienced at least one closure due to pollution in 2012. More than 20,000 beach days were lost, a statistic that has not improved since the start of EPA’s national beach monitoring program in 2008.

But you can expect better numbers in coming years because EPA has relaxed its standards. Steve Fleischli at Natural Resources Defense Council explains:

EPA recently adopted new, weaker water quality provisions for U.S. beaches . . . EPA’s criteria fail to protect against exposures to viruses, bacteria, and parasites on any given day. The prior criteria adopted in 1986 included a “single sample maximum,” which was not to be exceeded. EPA now allows water quality to exceed the criteria up to 10 percent of the time without triggering a violation . . . The criteria also are based on what the EPA has determined is an acceptable gastrointestinal illness risk of 3.6 percent. That is, the agency believes it is acceptable for 36 in 1,000 swimmers—that’s 1 in 28 swimmers—to become ill with gastroenteritis sicknesses such as diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, from swimming in water that just meets EPA’s water quality criteria

The July 1, 1983 fishable-swimmable goal of the Clean Water Act was about more than the protection of recreation, and fish and wildlife propagation. It was an “interim goal of water quality” that was intended to lead to “the national goal that the discharge of pollutants into the navigable waters be eliminated by 1985.”

Certainly, in retrospect, neither goal was practical or achievable. The naiveté of the 1970s is in evidence throughout the law. In an email conversation with EarthDesk, Paul Milazzo, author of the excellent Unlikely Environmentalists: Congress and Clean Water, 1945-1972, wrote:

Certainly, in retrospect, neither goal was practical or achievable. The naiveté of the 1970s is in evidence throughout the law. In an email conversation with EarthDesk, Paul Milazzo, author of the excellent Unlikely Environmentalists: Congress and Clean Water, 1945-1972, wrote:

[T]he ultimate goals of the act as stated were absurd . . . [Clean Water Act lead sponsor Senator Edmund] Muskie, against his better judgment, got carried away with the ecological language his staffers were selling him, and lost track of how those charged with administering the act were ever going to translate those goals and deadlines into practical policy . . . Many of the standards were unworkable from the start, and invited legal challenge. They should have known better.

Yet, remarkably, in the three decades since the top two goals of the Clean Water Act failed, neither has been reconsidered or revised, which only Congress has the authority to do. Because the goals are non-binding, it is now popular to characterize them as merely aspirational. But what direction does the Clean Water Act take now that it is empty of aspirations? We will continue to examine that issue in more detail in future posts. Below, some EarthDesk friends have weighed in:

David Cassuto, Professor of Law at Pace Law School; Director, Brazil-American Institute for Law and Environment (BAILE)

We should celebrate the audacity of a law that demanded all waters of the United States be fishable and swimmable by 1985. But we should not lose sight of the fact that the goal remains a grail and the deadline recedes ever further into the past. I hope that this thirtieth anniversary serves to reignite both the passion and the legislative will to reshape this landmark law into a means to actually guarantee clean water for people and ecosystems alike.

Shane Rogers, Associate Professor of civil and environmental engineering, Clarkson University. Formerly with the EPA, National Risk Management Research Laboratory in Cincinnati, Ohio.

For 41 years, we have been chasing a goal that is now 30 years behind us. Perhaps there was a hint of naiveté in its construction, but this goal remains inspirational and exigent. It is extremely curious that the regulatory pathway we continue to be led upon is outmoded, comparatively unimaginative, discouraging of innovation, and ineffective for contemporary water quality issues. It is abundantly clear that we need to look outward for innovation and leadership from those wise enough to invest in a new era of clean water.

John Parker, Environmental attorney, advocate and consultant and former Regional Attorney for the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation lower Hudson Valley-Catskill Region.

Three decades on, there remains much to be done to meet the landmark goals of the Clean Water Act. New York’s waterways have not been making the grade. Hurricane Sandy showed the stunning inadequacy of our water infrastructure that already causes our waterways to fail to meet fishable /swimmable standards. Innovation and investment are needed for these critical systems to become resilient and adaptable for our changing world. Now is the time and the opportunity for our waterways to get the focus they deserve – it is the only chance our waters have.

See our Fishing Gallery of Shame:

Click a pic to view gallery

Click a pic to view gallery