By Brett Walton

Circle of Blue

Editor’s note: Among the many things the outdated 1972 Clean Water Act did not anticipate is massive disposal of drugs into the nation’s waters. We include mandatory testing for pharmaceuticals in drinking water in our recent recommendations to EPA Administrator McCarthy (EarthDesk, October 23). But stopping the drugs at their source, and making drug companies pay for it, is the first line of defense. There are several pathways for pharmaceuticals to follow. One is down our toilets, to our local treatment facility, which cannot remove them, and then out to the receiving waterway. Some of those are unused drugs we simply flush down the toilet. Others are used drugs that moved through our bodies first. In this post, Circle of Blue’s excellent Brett Walton takes us through the story of the drug return programs of Alameda County, CA, and King County, WA, which, hopefully, point the way for the rest of the nation. This post also appears at Circle of Blue here. More on Brett and Circle of Blue at the conclusion of this post.. — John Cronin

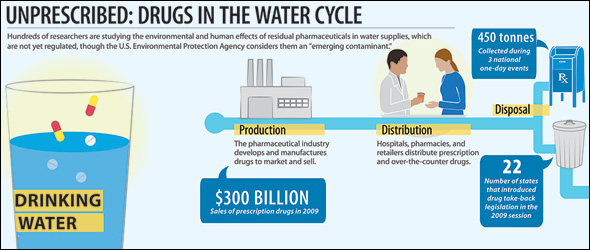

Unprescribed: Drugs in the Water Cycle infographic. Click image to enlarge, then click top right arrows. Infographic © Kelly Shea / Circle of Blue

During the summer of 2012, Alameda County, California, signed a first-in-the-nation law requiring drug manufacturers to pay for a program to collect and dispose of unused pills. The county, home to 1.5 million people on the east side of San Francisco Bay, was subsequently sued by the drug industry, which claimed a constitutional violation due to a burden on interstate commerce.

Two weeks ago, a U.S. district judge in San Francisco upheld Alameda’s program. Coupled with a similar law passed this June in King County, Washington, local governments are beginning to succeed where federal and state governments have failed in forcing drug manufacturers to foot the bill for disposal programs.

These take-back programs, most of which operate without industry funding, are designed to address a number of public and environmental health concerns: accidental poisoning from domestic stockpiles of old medicines and the accumulation of trace amounts of chemicals in water bodies from people tossing or flushing unwanted pills. The latter problem is the object of intense scrutiny from academic and federal scientists, who want to understand how the proliferation of pharmaceuticals affects both drinking water supplies and the aquatic species that are now living in an increasingly medicated world.

Take One

Despite the August 28 ruling in favor of Alameda County from U.S. District Judge Richard Seeborg, drug manufacturers remain opposed to paying for these programs.

“Though disappointed in this lower court’s opinion, we maintain our opposition to take-back programs like Alameda County’s, which place the entire responsibility on pharmaceutical manufacturers for the execution, finance, management, and administration of otherwise municipal operations, and shift the costs and burden of such local programs to out-of-county consumers and companies,” said the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) in a statement.

PhRMA, a plaintiff in the case, was joined in the lawsuit by the Generic Pharmaceutical Association and the Biotechnology Industry Organization, both industry lobby groups.

The plaintiffs estimated that a drug take-back program in Alameda County would cost $US 1.1 million to start and $US 1.2 million to operate each year. Alameda County — which claimed annual costs would be $US 300,000 — currently has 28 collection sites, most at hospitals and pharmacies. (Though controlled substances such as narcotics and antidepressants are accepted only at law enforcement offices, new regulations to relax that federal standard are in the works, thanks to a 2010 bill signed by President Barack Obama.)

Take Two

Meanwhile, King County’s take-back regulation is more comprehensive than Alameda’s. The Seattle-area jurisdiction accepts over-the-counter medications in addition to prescriptions.

In testimony during public hearings before King County’s regulation passed, the pharmaceutical industry threatened to sue the county, said Margaret Shield, a policy liaison for King County’s Local Hazardous Waste Management Program.

“The county had the political will to pass the regulation,” Shield told Circle of Blue, noting the unanimous vote.

Product Stewardship

Indeed, take-back programs funded by local, state, and federal sources have proved popular. Each U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration take-back day, held twice a year, sets a new collection record. Since October 2010, the DEA has received more than 1,270 metric tons (2.8 million pounds) of prescription drugs from the public in six such events.

The push for industry-funded drug disposal is part of a broader “product stewardship” movement in which governments, often with limited and unstable financial resources, are shifting the costs of disposal to the producers. At least 33 states have a law covering the disposal of one or more consumer good, according to the Product Stewardship Institute, a leading research and advocacy group. Most laws address electronics, batteries, and paints.

Industry-funded disposal programs similar to Alameda’s have been stymied in state legislatures, due in part to lobbying by the pharmaceutical industry. Legislation to establish a national industry-pays drug take-back program was introduced in the House of Representatives in 2011 by New York Democrat Louise Slaughter, but the bill died in committee.

What’s in the Water?

Concerns about accidental poisonings and drug abuse are domestic arguments for ridding medicine cabinets of expired and unused medications. The environmental argument centers on water resources.

Most wastewater treatment plants are not equipped to remove pharmaceutical compounds, hormones, and associated chemicals — not to mention that federal water quality regulations do not apply to these chemicals. When residual compounds enter rivers and lakes, there can be many sources for contamination:

- Some chemicals and compounds are not metabolized by the body. Residual compounds from medications are excreted in urine, while compounds found in skin creams can be washed off the body. For these sources, take-back programs would have no effect. In this same vein, the hundreds of FDA-approved chemicals in soaps, lotions, and other personal care products also play a role, as does the livestock industry, which pumps animals full of hormones and disease-blockers. It should be noted, however, that the pharmaceutical industry is working to develop medicines that the body processes more efficiently, so that less contamination of this sort occurs.

- Lacking an easily accessible venue for safe disposal, some people simply toss unused drugs in the trash or toilet. Improper disposal is assumed to be the smaller contamination source, accounting for a few percentage points to one-fifth of detected chemicals, depending on the study, Christian Daughton, the chief of the environmental chemistry branch of the EPA’s National Exposure Research Laboratory, told Circle of Blue in 2011.

Though the flow from each pathway is uncertain, evidence of drugs in waterways is ample and mounting. Even large lakes, where dilution was assumed to cleanse, are susceptible.

For instance, research published just last week in the journal Chemosphere found 32 chemicals from pharmaceuticals and personal care products in Lake Michigan within 3.2 kilometers (2 miles) of wastewater treatment plants in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The most common substances found were caffeine; metformin, an antidiabetic; sulfamethoxazole, an antibiotic; and triclosan, an antibacterial.

Researchers elsewhere are looking at how persistent exposure to small doses can turn fish moody and male frogs into females. Others are considering the effect on human biology or microbes, which, after living in pharma-water, might develop resistance to the very substances designed to kill them.

All told, take-back programs are a small but symbolic way to cut off one water-contamination path for the $US 320 billion prescription drug industry. Another way is to simply eliminate the source altogether, which is happening with greater frequency for personal care products — following the lead of fellow consumer goods giant Johnson & Johnson, Proctor & Gamble announced recently that it would stop using triclosan in its products by 2014.

«« »»

Brett Walton is a Seattle-based reporter for Circle of Blue. He writes their Federal Water Tap, a weekly digest spotting trends in U.S. government water policy. He has an MA in Central Asian Studies from the University of Washington and a BA in English from the University of Richmond. He has worked on a NASA-affiliated research project on water data and as a member of a State Department project on climate change and water management in Central Asia. His areas of interest are transboundary management, the political economy of water, and agriculture policy. When not writing, Brett can be found hiking in the Cascades.

Brett Walton is a Seattle-based reporter for Circle of Blue. He writes their Federal Water Tap, a weekly digest spotting trends in U.S. government water policy. He has an MA in Central Asian Studies from the University of Washington and a BA in English from the University of Richmond. He has worked on a NASA-affiliated research project on water data and as a member of a State Department project on climate change and water management in Central Asia. His areas of interest are transboundary management, the political economy of water, and agriculture policy. When not writing, Brett can be found hiking in the Cascades.

Founded in 2000 by leading journalists and scientists, Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

Founded in 2000 by leading journalists and scientists, Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

With an intense focus on water and its relationships to food, energy, and health, Circle of Blue has created a breakthrough model of front-line reporting, data collection, design, and convening that has evolved with the world’s need to spur new methodology in science, collaboration, innovation, and response. To get more water news, follow Circle of Blue on Twitter and sign up for their newsletter. More info on Circle of Blue here.